This discussion has reinforced my thoughts regarding turning a canoe with a heel vs carving and how it relates to carving a ski(s), which is how my brain thinks of carving. My conclusion is that there are two ways that canoes "carve" a turn and they rely on different aspects of canoe design and hull shape. Whether a canoe is carving in the first sense (turning towards the heel) depends on its hull profile when heeled, and carving in the second sense (turning away from the heel)

* depends on whether (and how much) the bow and stern stems extend into the water when heeled.

* "Carve. A deflected turn away from a heel, caused by differential entry edges and forces."

(Freestyle Canoeing: Contemporary Paddling Technique; Glossary of Freestyle Terms; 1996; Lou Glaros and Charlie Wilson.)

* "We can heel the hull... outside, away from the turn, starting the stems to carving."

(Freestyle Canoeing: Contemporary Paddling Technique; Part III, Chapter 10. Solo Freestyle Maneuvers, page 78; 1996; Lou Glaros and Charlie Wilson.)

* “[At the bow] the heeled down side intersects the water at a greater angle than the up side, and deflects the leading stem towards the side of less resistance.”

(Freestyle Instruction Manual Ch. 4 Pg. 6 Copyright 1995 CEW)

My alpine and Nordic skiing background has me thinking of carving a canoe (first sense) as heeling the boat towards the turn to narrow up the hull and produce a profile that very crudely mimics the shape of a fat powder ski. The narrower inside “edge” profile of the canoe carves into the water, acting like the compressed camber of a ski. Sharp edges (i.e., hard chines) might make the turn easier but are not required, thus there's a fair amount of skidding that occurs.

The other way that a canoe carves (second sense) works best when the stems, particularly the bow stem, remain in the water when heeled. The more stem that projects into the water the more powerful the carve. Narrow stems act like a tipless ski (with two bases) set sideways in the water. When vertical (sideways) it just keeps the canoe pointed forward, like a skeg, but when tipped to one side or the other it now acts like a high angle ski and carves away from the heel, using the pressure of water against the stem (ski base) to accentuate the carve. I think that’s why it feels natural to push down with my foot to emphasize the heel; it feels like I’m weighting a carving ski. And pulling up on the opposite foot feels like I’m unweighting the inside ski in a turn. In this case, the heeled profile of the hull is less important because the stems, especially the bow stem, is doing most of the carving, not the hull, and the stern stem is both carving and skidding into the turn, much like the tail of a ski.

So non-rockered canoes will have a much different response to heeling than a rockered canoe because of how much stem remains in the water. The stems act like a ski carving a turn and because the stems are oriented roughly 90 degrees to the hull they counter somewhat the yaw effect. That also may explain why a slim, non-rockered canoe tends to have less ability to turn into the heel, the stems continue to influence the forces acting on the canoe hull. Depending on hull profile and length, there is a wide range of effects; it’s all relative.

That’s how I think of carving a canoe. I use carving in the second sense to subtly offset the yaw effect when paddling a fast solo touring canoe. Flame on!

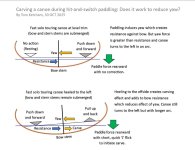

The following diagram shows what I believe is the difference between a typical hit-and-switch forward stroke with no heel vs a hit-and-switch forward stroke using a subtle carve to partially offset yaw.