Camp 25 km (15 miles) north of (below) the Napaktolik River. According the the Paddling Guide to the Northwest Territories, near the confluence of the Coppermine and Napaktolik is a set of four rapids over an 8 km (five mile) stretch that is the first real white water challenge on the Coppermine. We ran the first three fairly easily, although the water was pushier than I expected.

The real difficulty for us occurred in the Class III rapid in the west trending portion of the Coppermine, about 5 km (three miles) below the Napaktolik River. As we approached the rapid from up against the left bank, Carey suggested that we back around a very large rock jutting out from shore. The rock outcrop was large enough that we could not see what lay behind. Our experience had virtually always been, however, that an eddy lies behind such large rocks projecting into a river.

The Coppermine is a big river, with impressive hydraulics. We backed around, quite nicely, I might say. But there was no normal, calm eddy behind the boulder. Instead, as the Coppermine raced around the boulder, it filled the void behind the boulder by reversing its current. We were immediately thrust back out into the main current and were now headed toward the middle of a rapid that did not look like anything Kathleen and I would ever want to run. Particularly on a wilderness canoe trip. This did not look good.

I know people often exaggerate their exploits, but I am telling you the truth. Huge holes and diagonal waves reared up to greet us. There were no downstream Vs or any apparent routes through. We would just have to wing it and hope for the best. Kathleen and I plunged over a ledge and into a hole that seemed like a 1.5 m (four feet) drop. We powered out of the hole but were slammed by a diagonal wave that spun the canoe around. We were still upright, though.

I turned my head around to see that we were hurtling toward another hole, perhaps larger than the last. As you can imagine, we did not like the idea of plunging into holes or over ledges going backward. Our stern was now passing by a wide boulder with a somewhat calm eddy behind it. Calmer than the current, anyway. That was all we needed. I plunged my paddle into the eddy, held on, and the boat swung around, like swinging around a fulcrum. We were now going bow first. That was very good. The bow glanced hard off the edge of a boulder and plummeted into a huge hole below. Our spray skirts blew off the cockpit coaming, and water poured into the canoe.

Still upright, though. We could see Carey and Janice, on river left, up against a cliff bank. They were bailing water in a very small eddy, perhaps no wider than a canoe. We headed over, hit the eddy (in the normal way), and bailed the water out of our canoe.

We looked downriver. We were only about halfway through the rapid. Janice looked at Carey and said, I am not getting back in the boat.

I do not remember if Carey replied. Did not really need to. Everyone had to get back in the boat. We were up against a steep, high cliff. There was no real shore that we could walk on to line the boats. The only way out was to paddle the rapid.

We forward ferried 100 m (100 yards) across the river to put ourselves beyond the huge haystacks at the bottom of the drop. We then turned down and finally reached calm water on river right. We beached our canoes and got out to rest our nerves. Janice was shaking, claiming that it was the most horrendous rapid she had ever run. And that was saying something. On many day trips with our Beaver Canoe Club, we had seen Carey and Janice paddle stuff that Kathleen and I only sat on shore to watch. This rapid is one of the three times I have actually been worried on a northern canoe trip.

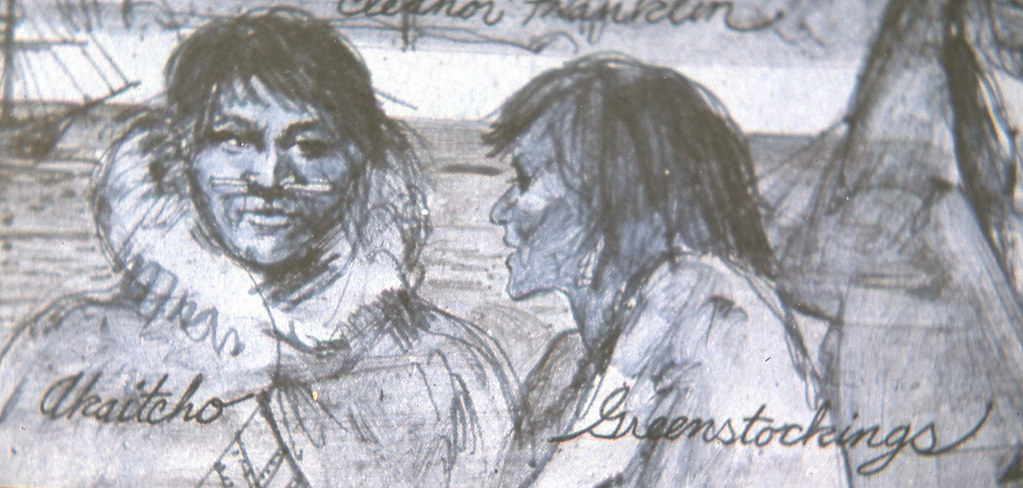

Samuel Hearne was the first European to travel to the Coppermine, reaching Bloody Falls in 1771. He had tried and failed on two previous occasions to reach the Coppermine River from Fort Prince of Wales on Hudson’s Bay.

For his third attempt, Hearne arranged to be led by the native hunter Matonabbee, who was shocked to hear that the British did not travel with women. Matonabbee explained his position.

For when all the men are heavy laden they can neither hunt nor travel any distance. And in case they should meet with some success in hunting, who is to carry the produce of their labour? Women were made for labour. One of them can carry or haul as much as two men.

They also pitch our tents, make and mend our clothes, keep us warm at night. In fact there is no such thing as traveling any considerable distance without their assistance.

More than this, women can be maintained at trifling expense, for as they always cook, the very licking of their fingers in scarce times is sufficient for their sustenance.

I like to believe that the perspective held by Matonabbee reflected the immeasurable value of women to the success of nomadic societies. European diaries, written by the expedition leaders such as Franklin, largely ignored the contributions of people who did most of the work, and who provided all of the local knowledge and expertise.