Deerfly,

The people at Colville would have been very happy to share their knowledge with you. Too bad you weren't there! One group of our visitors in the spring asked us if we got any caribou during the winter. I told them that a person has to be a resident of the Northwest Territories for six months before they qualify for a licence to hunt. They sort of shook their heads, and said, "No one would say anything if you were hunting for food."

Christy,

It sure ruined us for city living! And, you can live in the bush without making it so physically demanding. We could have just hunkered down. Didn't have to put in all those snow trails. Didn't have to cross the ice to town. Could have made it a lot easier on ourselves.

Doug,

Things were still going quite well at 9 p.m. Thanks for asking!

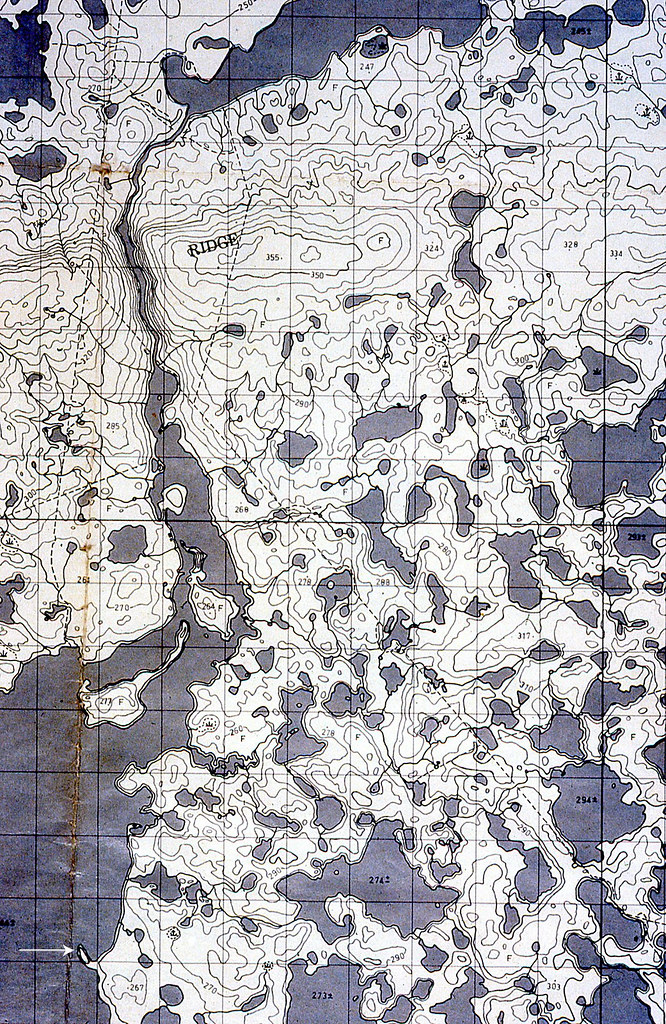

Four km (2.5 miles) later the ice lay rafted up against a narrow point that projected into the lake (Note the white arrow, bottom left). No open leads. We forced our way to shore, beached the canoe, unloaded all the gear, and portaged 150 m across the tundra-like point, where Cloudberry and Bog Rosemary were beginning to bloom.

Just as we finished the portage, Richard, Tommy and Greg arrived in their aluminum powerboat, forcing their way through the thick ice. “We were out hunting,” they said, “and happened to see you here.”

Richard, Tommy and Greg had all been in the tent when we left about an hour ago, and didn’t mention anything about a hunting trip. I think they had actually come mostly to check up on us, to make sure that we were OK. Nevertheless, they had just recently shot some Long-tailed Ducks (“Oldsquaws").

While Kathleen and I snacked on smoked fish, our three visitors prepared their dinner. Their approach to camp cooking differed markedly from ours. We would normally prepare a small fire pit encircled with stones. I would then collect some small, medium and larger-diameter pieces of wood, which I would saw into appropriate lengths. If I had known how, I would then gut and de-feather the birds and put them in a pan over a grate on the fire. This method sounds good, but in reality is unnecessarily complicated.

Our three visitors made no fire pit encircled with stones. They simply dragged in a large pile of wood of all and various dimensions and set them on fire. Then, with small sticks, they impaled each of the birds through the throat, placed them around the perimeter of the blaze, and sat back to enjoy their tea. Bits of fire began to run off away from the camp. No one seemed concerned. The bush was still too wet for a wildfire to break out. After about 30 minutes the birds were declared done. The seared feathers rubbed away easily from the charred skin. The birds were then ‘opened’ with a knife, and the guts simply fell out. This simple approach required minimum effort with very few supplies. Just a knife and some matches. No grate. No pots and pans. No axes. No saws. Quite opposite to the high-tech approach used by most urban visitors to the wilderness.

After an enjoyable hour of conversation and tea, Kathleen and I paddled away into absolute calm and quiet. The midnight sun, still high above the northern horizon, shone hot upon our backs. The calls of Common Loons and Oldsquaws beckoned us south. We slid between the sunlit, golden shoreline on our left and the white, silent, rotting ice sheet to our right.

We stopped at 1:30 am and set up our tent in a well-used camp on an open terrace overlooking the lake. At 2:30 we fell asleep instantly, serenaded by the calls of White-crowned Sparrows. I slept soundly, without waking, until 11:45 am.

On June 10,

we awoke to a sunny, calm, warm morning. Just like yesterday morning, we still live at Colville Lake. But our life differs very markedly from yesterday. Now that we live in a tent rather than a cabin, our senses are so much more alive, so much more a part of our surroundings. We are no longer walled off from the natural world. We see and hear Arctic Terns diving and plunging into the lake. We hear ice shards tingling in the distance. We hear waves caressing our cobblestone beach. We feel the touch of a gentle breeze on our faces as we cook breakfast bannock over a fire that crackles so very reassuringly. And still no mosquitoes. Again I ask, how can life be better than this?

After breakfast we paddled toward the next point, 5 km (three miles) away, to see how far we could get before being blocked by ice. This east/west point extended even farther into Colville Lake than the previous ice-bound point, and through our binoculars at breakfast we thought that we could ‘see’ ice blocking the shoreline.

“Let's just go and have a look,” we said. “No need to pack up. We probably won’t be able to get through anyway.”

Ninety minutes later we rounded the point in a 100-m wide lead of open water, and could see apparently unending open water down the shoreline to the next distant point. We returned to camp, now knowing that barring a major wind from the northwest, we can probably reach town tomorrow.

We sat in front of the campfire sipping tea. Should we leave for town now, at five o’clock? If so, we would arrive when everyone was sleeping. Should we rest until midnight, and then head out? I love paddling beneath the midnight sun, and we would reach town around 7:00 am, just in time for breakfast. Or should we get a few hours sleep first, and put on the water early by 2:00 am, before the wind has a chance to block the open lead? We don’t know what we’ll do. And that’s the beauty. There is no night. There is no day. There is no right way. There is no wrong way. For now, we'll just sit by the fire, periodically poking in more logs. We'll head to town when we feel like it. No later, and certainly not before.

On June 11, we headed down the east shore, south toward the point, just after breakfast, about 10:00 am. Again we found open water, with nearly 150 m (yards) between the shore and the ice sheet. A mild northwest wind now helped push us forward. We continued paddling around the point, toward the next point, 2.5 km (1.5 miles) away, where ice clogged our route, and lay rafted up, in large broken chunks against the shore. We beached in a small cove within the icy jumble, and walked along a ridge covered in scattered spruce and Bog Birch to assess the situation.

Again, Northern Labrador Tea smelled so very sweetly as we surveyed the ice, which extended nearly 1.5 km(1 mile) in an impenetrable barrier. We returned to the boat, and relaxed on shore, sipping tea, and gnawing on smoked whitefish. We concluded that unless the wind shifted to the southeast, to push the ice offshore, we would likely need to camp in a small clearing 200 m (yards) up into the bush.

We heard a motor approaching from the north, and twenty minutes later Richard, Tommy and Greg landed for coffee and conversation. They reported that the northwest wind was moving the ice back on to the east shore of Colville Lake. The open leads through which we had paddled so easily only hours ago were now clogged with ice; our visitors had spent most of the morning forcing their way through. We lounged for a few minutes, and then they continued south to drop off some gear at an intended camp, slowly struggling through the pack with their powerboat.

We followed 10 minutes later in their broken lead, which was already closing up. Only half way through, 100 m (yards) from shore, the ice squeezed shut, and held us firmly. We knew that the powerboat would be returning soon, so we sat patiently, listening to the candled ice of a new spring. In mid-winter, the surface of the snow is colder than lower in the profile. As the days become warmer in spring, the temperature gradient in the snow cover reverses; the surface is now warmer, and melts during the heat of the day. Water then drains down through channels in the upper snow crystals, which turn into long, vertical cylinders called ablation needles. The result produces a musical tinkling when these prism-shaped needles rub against each other. It was as though we were sitting in a giant field of wind chimes, as we swayed back and forth in the gentle breeze.

Fifteen minutes later the powerboat returned, and again opened up a narrow, chaotic, serpentine route. Richard, Tommy and Greg wished us luck as they crunched their way north, and we slowly paddled south through the closing lead. Only two canoe lengths from open water we again became hopelessly mired as a thick, unbroken chunk of ice fell into the last remaining lead. Thirty minutes of ramming, poking, rocking, prodding, banging, and prying eventually freed us from the pack, and we once again paddled into open water.

The next point lay only one km away. By now we were suspicious of all points, which seem to collect ice like magnets. Our suspicions proved correct, for as we rounded the point, ice completely filled the 1.5-km (1 mile), shallow, scalloped bay to the south. We paddled back to the north side of the point, where we beached, collected firewood, and prepared and ate our cheese and pasta dinner. We then strolled along the ridge, where Cloudberries, Bog Rosemary and Lapland Rosebay bloomed among the tussocks of Northern Labrador Tea. We climbed up an open, tundra-like terrace to stand before a low, four-sided picket fence. Inside, the single wooden cross marked a grave that had been beautifully located to overlook Colville Lake. To the south, toward town, we could see nothing but unbroken ice. Kathleen and I returned to the canoe along the bay, along a shoreline that had no open leads. We seemed to be stuck.

The wind continued to blow from the northwest, and Kathleen wondered if we should just set up the tent and camp for the night.

“I don’t know,” I said. “It’s not a great place to camp, I’m not really sleepy or tired, and I don’t feel like putting up the tent. Maybe the wind will shift.”

“It’s been blowing in the same direction all day, Michael. It’s already eight o’clock, and there’s no sign that the wind is letting up. I don’t want to put the tent up either, but I don’t want to just sit on the shore all night.”

On one of Richard’s visits to our cabin we had mentioned how spectacular the Northern Lights had been for most of February and March. Richard commented that “when a man is all alone on the winter trail, he can whistle for the Northern Lights to come closer.”

“So you know, Kathleen, if Richard can whistle for the Northern Lights to come closer, then maybe I can whistle for the southeast wind to blow.”

I whistled meekly, not wishing to challenge the universe. We sat and watched tiny bits of ice floating along the shore. Moments later they stopped, then reversed their direction and twirled back up the shoreline as the wind shifted to blow from the southeast! Large rafts of ice out on the bay now showed lee water along their margins. Arctic Terns began diving into what must be small patches of open water on the still ice-filled bay to our south. Red-breasted Mergansers and scoters (Black Ducks) landed and fished in slivers of leads. Twenty minutes later the entire shoreline opened up as the pack drifted out from shore.

It’s not possible to know why the wind shifted just as I whistled. Kathleen says that she was simultaneously praying for the wind to shift, meaning that the experiment was confounded. Also, there was no ‘experimental control,’ in that we had no data for what would have happened without either whistling or praying. All I can say is that I whistled, Kathleen prayed, the wind shifted, the ice moved, open leads appeared, and we continued our journey south to town at 9:00 pm.

We rounded the point to enter the shallow, scalloped bay that still contained some ice at its north end. We sluiced our way through gray slush, forced our way through disintegrating, candled rafts, wedged our way through cracking chunks, and in only 20 more minutes paddled away into open water, now apparently without end.

We canoed snugly up against the shore in the lee of the continuing southeast wind. The calm lake surface reflected the shoreline dunes and stunted spruce, which glowed in the midnight sun. The gray, brooding ice lay harmlessly 200 m (yards) to the west. Perhaps we will reach town tonight. At 12:30 am we again encountered very thick, nearly unbroken ice on the cape 5 km east of town. We powered into and up onto a 25-cm-wide (10 inches) crack, where we rocked up-and-down and back-and-forth until the ice surrendered, split open, and allowed us to pass.

We continued west, along the south shore, now expecting to reach town. At 2:00 am we approached the headlands, which lay encased in ice. We paddled along the entire margin of the pack, hoping to find a route through. No passage existed, however, and we turned back to shore just in time, as shifting ice was already closing in behind us. We rammed through and beached the canoe at the ski-doo trail, 1.5 km from town, at two-thirty in the morning.

We walked into town, almost expecting an enthusiastic reception. The town site was empty though, almost deserted; everyone seemed to be either away or in bed. We returned to the canoe and began unpacking. By 5:00 am we had completed portaging all our gear to Bern Will Brown’s compound. Still no one up to greet us. No one to invite us in. What should we do? It didn’t seem right to disturb anyone. So we just strolled around town, between Bern’s lodge and Robert and Jo-Ellen’s house, hoping someone would look out their window and see us. We had made several circuits by 6:00 am, but still no one had seen us. We played on the swing set. Still the town remained quiet and asleep. We made several more rounds.

Finally, at 7:00 am, we heard rustling in one of the lodge’s cabins. On our next pass, the curtains were open, and Margaret’s sister, Agnes, who was in town working and preparing meals at Bern’s lodge, spotted us. At 7:30 we were seated at the table in the main dining room, dining on a fantastic breakfast of eggs, bacon, toast, juice and coffee. Thank you, Agnes!

I thoroughly enjoyed the past two days. I loved seeing, playing with, and being with the ice. I savoured paddling beneath the marvellous light of midnight. I am very satisfied to know that I can still paddle all day, throughout the night, and yet still have enough energy to portage 2.5 hours across boggy ground. We had left the Tent Camp on The Big Island on the evening of June 9 ‘just to see what happens.’ What happened was a fantastic two days. Thank you, Marie!

On June 12, we spent the day wandering around town, greeting people who now know us from all of their visits since duck hunting season began. It seems that we have been accepted as part of the community. Everyone knew of our trip and progress to town because of ‘Native Radio.’ All were happy to see that we had arrived safely.

People were disappointed though, that we had wandered around town for three hours in the early morning, just hoping that we would be spotted. Agnes said that, “We were worried about you. Bern said not to worry. That you were fine. That you knew what you were doing. That it’s a nice time of year, and you were probably just camping. But we were worried. You could have knocked on any door in town, and people would have let you in.”

We could have knocked on any door in town, and people would have been happy to let us in. It never occurred to us that we could have knocked on any door in town. Think about it. We could have knocked on any door in town. Even on the doors of people we didn’t know, and they would have welcomed us in. I am reminded of another of Rene Fumoleau’s stories, entitled

Dene Christmas. Father Fumoleau had arrived in Fort Good Hope [Radeli Koe] in June of 1953. Here he met John, a Dene in his early twenties. Father Fumoleau admired John’s art, and asked John to draw the Christmas Story as though it had happened in Fort Good Hope. The two men agreed that the drawing should feature local and native themes, in that Joseph and Mary would arrive by a toboggan pulled by four dogs. Mary and Joseph, after finding no room in town, would pitch their tent on the other side of Jackfish Creek, where Jesus would be born.

After a week, Father Fumoleau asked John how the drawing was coming along. “I’ve been thinking about it a lot,” John said. Another week went by and John said he was still working on the drawing. Weeks turned into months and Father Fumoleau asked John directly if the drawing would be ready in time for Christmas.

“I don’t think so,” John replied. “I mean, that drawing doesn’t make any sense to me.”

“Oh?”

“You see, if Mary and Joseph had come to our village, they could have walked into any Dene house, and the people would have said, ‘Come on in, you’re welcome.’ ”

On June 13, a Sunday, we spent an uneventful day. Emails. Phone calls. After church we walked to the airstrip, up on the terrace east of town. From there we could see that all the ice has been moved off shore by the continuing southeast wind, which blows more strongly with each hour. The route to our cabin along the east shore of Colville Lake gapes wide open. We hope to leave Tuesday morning.

This afternoon Bern volunteered to come to North End by powerboat to take all of our winter gear back to town. Now we just need to make arrangements to get the gear from Colville Lake to Inuvik.

On Tuesday, June 15, we enjoyed another one of Agnes’ sumptuous breakfasts of eggs, bacon, toast, juice and coffee at the lodge. Three other guests joined us at the table, including a representative from North-Wright Airways in Norman Wells, with whom we made arrangements to fly our winter gear from Colville Lake to Inuvik. Our business in town was now complete, and we set out for home at 10:30 am. The cape no longer lay encased in ice, which was barely visible far to our west. We paddled around the point into a warm, southeast breeze, barely aware of the mosquitoes clinging to our backs, and flitting about our heads.

The shallow lakeshore mirrored the puffy-clouded, sun-drenched sky above. A golden-green light suffused through the placid water, penetrating easily to the sandy bottom half-a-metre below our canoe. Cloud-shadows hypnotically wavered and played on the sandy rills. Our rhythmic strokes took us from one hour to the next, one ice-free point to the next.

About halfway down the east shore we stopped for dinner between two points where the shore gradually merged with the land. Open, park-like stands of spruce had beckoned to us, inviting us to linger on carpets of flowering Kinnikinnick, Crowberry, crunchy layers of lichen and soft layers of deep green moss. We resisted the temptation to camp in what was certainly the best campsite between town and the north end of Colville Lake. We were too close to home to stop now. Only 25 km (15 miles) to go.

We paddled on, in open water, where only five days ago we had battled thick rafts of often-impenetrable ice. The temperature hovered at 30 C (86 F). Increasing swarms of mosquitoes brought out the DEET repellent. Summer had arrived with an unbridled passion.

By 10:30 pm we neared James and Sharon’s new cabin. We paddled down the east side of the Big Island in its protected, calm water. Near its shrub-covered northern extension hordes of mosquitoes forced a temporary halt to apply generous amounts of DEET to our exposed arms and face.

At the exact moment of midnight, just like Cinderella, we beached our canoe in front of our cabin. We were home. A relaxing 13.5 hours to paddle approximately 40 km (25 miles). We felt energetic, and seem to be in good physical shape for paddling to the Arctic coast.

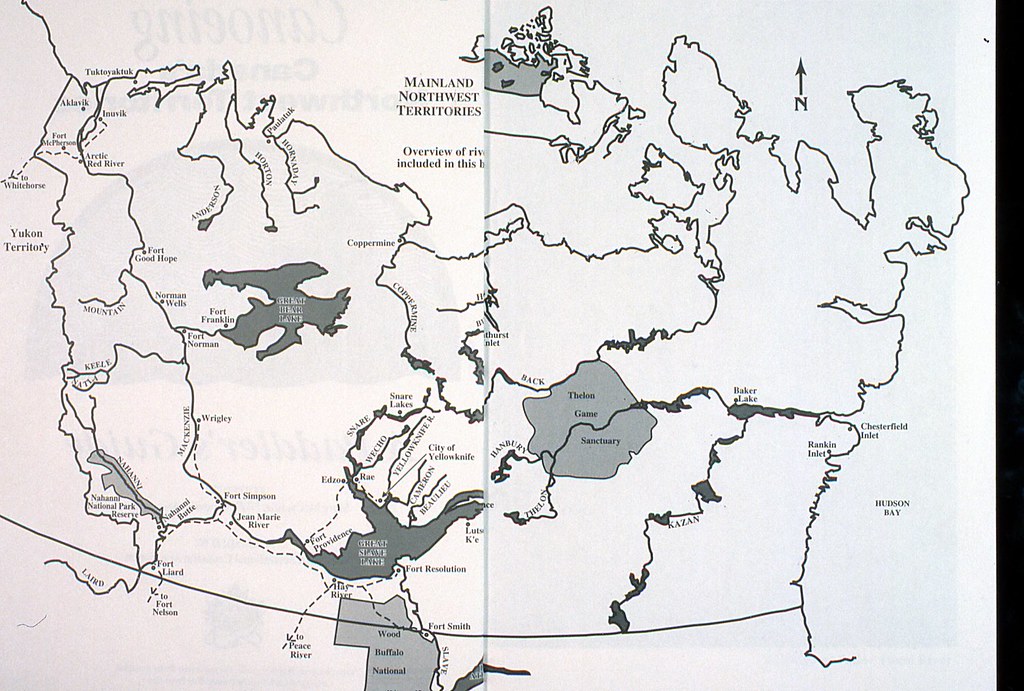

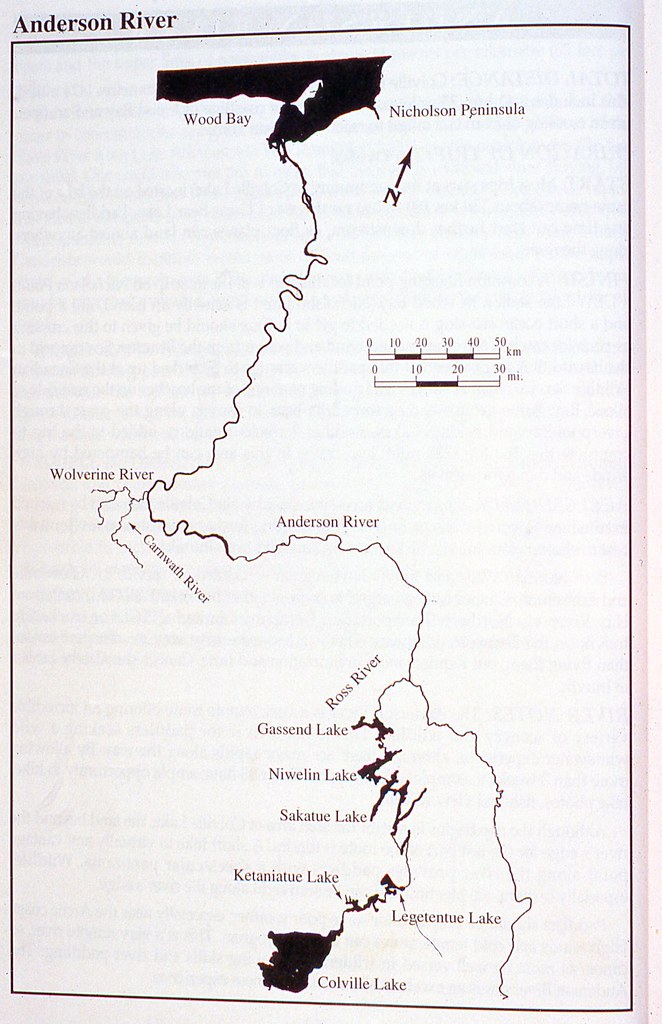

Much had changed since we left six days ago. The Trembling Aspen and Balsam Poplar tress had leafed out. Red Bearberry had sprouted thick leaves. Prickly Saxifrage, Northern Comandra and Arnica were all blooming. Even at midnight, the temperature of our cabin interior registered 22C (45 F). Mosquitoes buzzed about our heads all night. Summer has arrived. In many ways, today was the first day of our canoe trip down the Anderson River to the Arctic coast. Our winter adventure – our sojourn into ice-bound isolation has ended. Vancouver threatens us in the not too distant future. I feel disconsolate, and wish we could return to last January 31st, when Kathleen and I first stood on the ice, all alone, surrounded by silence, trepidation and excitement.

On June 16, we spent the day cleaning up, washing clothes, repairing gear and studying our maps of the Anderson River. Over the course of the winter we had accumulated six bags of garbage, mostly cans. We had burned all paper and cardboard garbage in the wood stove, and had given most of the organic garbage to the mink that lived in the burrow along the east shore north of our cabin. I had assumed that Bern would be taking our garbage back to town, but during last night’s radio conversation he said, “No, just burn it. You’ll find a garbage dump, in a pit about 100 yards northeast of the cabin.”

I found the garbage dump, and spent a couple of hours flattening and then burning the cans. Six bags of garbage aren’t very much for five months, certainly much less than we would have accumulated in five months back in Vancouver. But I didn’t like the idea of leaving my garbage here at the north end of Colville Lake, which seemed so pristine. This spot didn’t deserve garbage. In reality, though, it doesn’t make much difference whether my garbage gets dumped in town or here at the cabin. It’s still garbage. It has to go somewhere. It’s my garbage, and it’s my responsibility to deal with it.

The weather continued unbearably hot to be outside, particularly in front of a hot fire. Kathleen strung mosquito netting above our bunks; hopefully, tonight’s sleep will be uninterrupted and more relaxing.

June 19 was our last full day at the cabin. Our last day of life at North End. Distant gunshots from hunters chasing geese and swans woke me, and I stepped outside at 4:30 am. I stood alone and silently outside on the south dock. A Bald Eagle soared majestically above Colville Lake. A beaver swam confidently through The Narrows of the outlet. A northern pike broke water aggressively in the shallow warmth off our north dock. Palpable, quiet sorrow at leaving an idyllic winter of solitude and adventure. In a little over 24 hours we will paddle away forever from our cabin. It will then be the end. Sadly, this is the end – the end of what has been the most satisfying period of my entire life.

At 2:30 p.m., on June 20, our gear was packed, and both cabins locked and shuttered – just like we found them last January 31st. Kathleen and I wandered one more time around the compound. We walked along Laundry Lane and Lower Cabin Crescent. We sat below the flagpole and looked south across the wind-rippled surface of Colville Lake. I could have cried without too much prompting. I sighed deeply as we slowly made our way back past our cabin with its wood stacked neatly, 2 m (6 feet) high on the porch.

We continued down the hill to our loaded canoe, which bobbed slightly in the afternoon breeze.

We looked at each other. What could we say? “It’s over. It’s time to go.”

I felt no joy, no excitement – only loss. Kathleen and I paddled away toward the Arctic coast. We could not bear to look back.