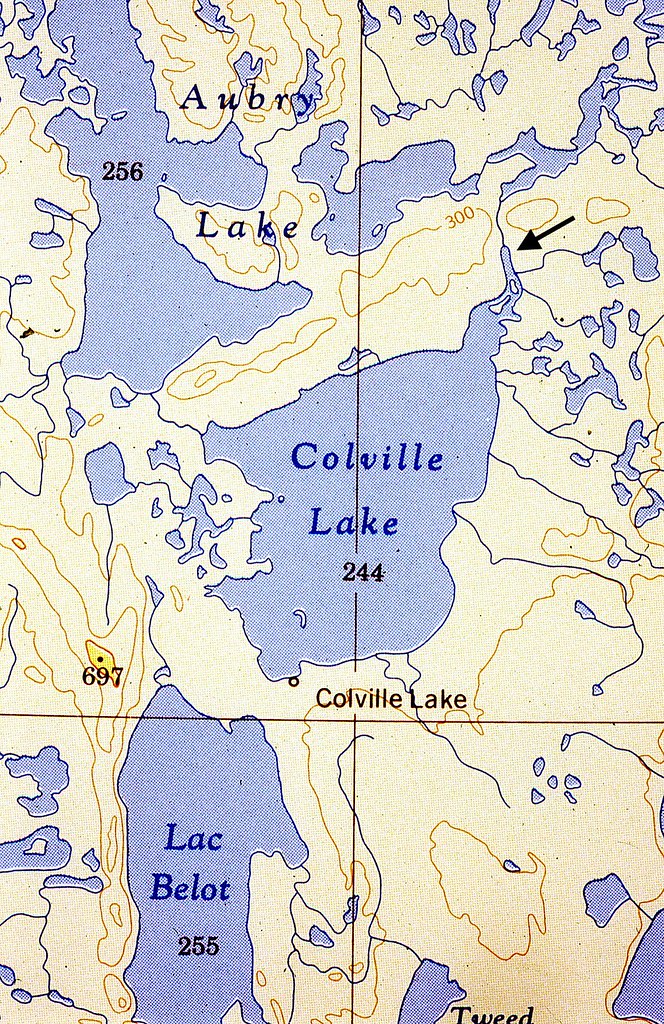

Bob flew low over the cabin, banked sharply, then turned back south, descending slowly toward the surface of the horseshoe-shaped bay illustrated on Bern’s map. Bob had never landed at Colville Lake in the winter, and despite Bern’s map, was unsure of how thick the ice might be. Bob’s voice crackled through the headphones: “I’m going to just skim the surface of the snow with the landing skis, and take off again. Then I can circle back to see if any water has wicked up into our tracks. If I see wicking, the ice will be too thin to land.”

The plane’s skis knifed two parallel tracks into the newly fallen snow. After maybe 300 metres the pilot opened the throttle, and the Twin Otter gained altitude toward the south. After banking east, and then circling back north, all of us could see that the plane’s tracks shone pure white in the early afternoon sun. No evidence of wicking. The ice was probably thick enough to land our heavily-laden plane.

We circled once more, and approached from the south, again descending slowly until we finally touched down on the snow-covered ice. The Twin Otter skied north, along the east shore of the horseshoe-shaped bay, until it stopped a few hundred metres (yards) away from our cabin at the lake’s outlet. Kathleen and I had finally arrived!

Co-pilot Bob lowered the stairs and he, Kathleen and I stepped down onto the snow. Seconds later, pilot Bob started handing out storage bins, packs, canoe, sled and the rest of the supplies we would need for the next six months.

“Make sure you spread this stuff around. I don’t want all this weight concentrated around the plane.” He seemed anxious to get away again.

“Before going, can you wait to see if our key to the cabin actually works? We want to make sure we can get in.”

“Don’t worry. I’m not leaving you out here until I know you can get in the cabin, and that you can make a fire. Do you have any matches?”

“Yeah, I have a lot of matches.”

“Show them to me. I want to make sure that they’re handy.”

I reached into my shirt pocket and held out two boxes of strike-anywhere wooden kitchen matches. I always carry plenty of matches. I always keep them handy. It was good to know, though, that the pilot was concerned about our safety – very professional and reassuring.

Kathleen said that she wanted to try the key right away, and reached inside her parka to check yet one more time that the cabin key was still dangling from a cord around her neck. She then headed off through the snow, sinking in up to her knees. After only a few steps she returned to search in the growing pile of gear for her snowshoes. She laced the lamp wick bindings around her mukluks and strode easily across the lake, looking very much like she belonged.

By the time Kathleen came back, all the gear had been unloaded, and our pilot and co-pilot were sitting on a storage bin, smoking a final cigarette before departure.

“So the key worked?” I asked.

“Yeah. The lock turned easily. No problem at all.”

I could tell from the satisfied look on Kathleen’s face that she was happy with what she had seen so far. The cabin must have appeared clean and livable.

The Bobs finished smoking their cigarettes, shook our hands, and said, “See you later. Have a great winter. Hope everything goes well.”

They climbed back into the Twin Otter as Kathleen and I moved to one side to avoid the backdraft of the propeller.

The plane burst to life, roared across the surface of the lake amid billows of white, and lightly lifted above Colville Lake. Four minutes later Kathleen and I stood all alone, surrounded by a silent world of snow, ice and cold. I checked the thermometer clipped to my daypack. Minus 19 C (-2 F). I stepped into the bindings of my snowshoes, and contentedly followed Kathleen toward our cabin.

Our freshly-minted snow trail led to the south side of the point where our cabin sat about 10 m above the level of the lake. As we approached the cabin, I was happy to see wood, stacked neatly about 2 m (6 feet) high, on the porch next to the door. I pushed the wooden door inward, and a small shaft of light penetrated the otherwise dusky cabin interior.

An oval, wood-burning stove rested on a 25-cm (10 inch) platform in the centre of the cabin, next to a wooden box already filled with newspaper, kindling and split lengths of wood. The stove seemed kind of small for winter, though, and wasn’t much over 40 cm (14 inches) tall, and not much bigger around. Bern had told us that the cabin was not intended for winter use. I took the box of matches from my pocket, and quickly and easily started the fire.

In a few minutes our new home began to warm, and I filled the stove with more wood. Kathleen scooped some snow into a pot and set it on the stove to make tea. We sat at the table, just resting and contemplating. There was a lot to do to prepare for the night. First of all, I wanted to move all of our gear and supplies off the lake, and up to the cabin. Kathleen suggested that we didn’t have to move everything today. “We need only to bring the essentials, Michael. The rest can wait until tomorrow.”

She was right, of course, but I’m always worried about leaving supplies out in the open. I was particularly worried about leaving supplies so far away, out on the ice. What if the ice was thin, and opened up during the night? What if wolves or wolverines came during the night, and made off with our supplies? All of our supplies are essential. We need every item in every one of those bins sitting out on the lake.

So we spent the next 3 to 4 hours sledding and tobogganing all of our gear 200 metres (yards) from the landing spot up the hill to the cabin. We left much of it outside, as there was not nearly enough room inside the cabin, which Bern told us measured 14 x 14 feet from outside wall to outside wall. Most of that small space was already filled with tables, chairs, bunk beds and counters. At least our supplies are nearby, though. They can’t slip through thin ice now, and I should be able to hear any marauding wolves or thieving wolverines. Like most suburbanites, I am not a hunter. I have come to see wildlife, not to kill wildlife. But I did bring my rifle, and I am ready, as I must be, to protect what is mine.

It was now about 6:00 o’clock. We were both a little tired after so much physical work. We were also experiencing the natural unwinding that always occurs when a much-anticipated event has finally happened. The southern horizon glowed with a protracted sunset. Kathleen and I were ready to call it a day.

Kathleen lit some candles, sliced several pieces from Dave’s home made bread, and set out a plate of cheese and dried caribou. We ate our sandwiches and sipped tea, enjoying the warmth of our fire. We stepped outside to check the thermometer that we had hung on the northwest corner of the cabin – still -19 C. A rising blue moon began to brighten the night sky. A beautiful way to end our first day at Colville Lake. At 8:30 we spread our sleeping bags out on the lower level of bunk beds. I filled the stove with 25-cm (10-inch) long spruce logs, blew out the candles, and quickly fell asleep.

On our first morning, I woke at 10:15, climbed out of my bunk, lit the candles, and peered at our indoor thermometer, which read +8 C (46 F). Not too bad, I thought. Still fairly warm. I stepped over to the wood stove, which was nearly out, and stuffed in some kindling. I opened the circular air intake, and placed a lighted match to the newspaper. The kindling ignited, the stove sputtered, and the heat radiated outward in concentric circles.

I walked over to the propane stove and turned the left knob. The automatic ignition clicked, but no flame appeared. I checked the connections, and tried several more times. Lots of clicking, but still no flame. I couldn’t smell propane, so maybe something’s wrong with the tank. Maybe the tank’s empty! That would be very disappointing.

I stepped outside into the screened porch to check whether the propane cylinder release valve was open or closed. dang. Someone’s locked the cylinder cap on the propane tank. Bern never said anything about the propane cylinder being locked. There better be a key around here somewhere. I don’t want to be the one to tell Kathleen that we don’t have fuel to operate her kitchen stove. She’s not going to like that. I don’t like that prospect very much myself. The surface of the wood stove is small, and not useful for much more than boiling tea water.

I searched through the 10 or so keys hanging just inside the door, suspended from nails on well-marked, 15-cm-long wooden key chains. ‘Boathouse.’ ‘Tool Shed.’ ‘Cabin.’ ‘Upper Cabin.’ Nothing identified itself as ‘Propane Cylinder.’ One key, though, dangling from a small wire loop, was unlabeled.

I felt a great deal of relief when the key fit, and smoothly turned in the padlock. I unscrewed the cap, opened the valve, and walked back inside to the stove. I smiled smugly as the ignition produced an instant flame. One unexpected challenge already dealt with successfully. At least now we can have some hot oatmeal for breakfast.

Kathleen was now up, and we closely assessed our new home. The cabin was better than we ever imagined it could be. A picture window faced up Colville Lake, south toward the winter sun. A reading and writing table sat below the window. On the corner of the table was a spot for the SSBx-11A radio, where we could attach it to the antenna and ground wire protruding through the south wall. A double row of bookshelves hung above the window.

The west wall featured the door and a semi-circular dining table, above which a nine-pane window would admit views of the setting sun in spring. Open shelving, supported by angled struts, provided storage for pots, pans and skillets above the window. Other domestic paraphernalia such as brooms, dustpans and two white-gas Coleman lanterns hung from various hooks and nails. The cabin was completely stocked with cutlery, dishes, linens, canisters and other household necessities. Curtains framed the windows.

Cupboards, breadbox, counter space, a propane refrigerator and the two-burner propane stove graced the north wall. A wash basin and mirrored medicine cabinet fit snugly and neatly into the northwest corner. A pair of three-tiered bunk beds lined the east wall.

A drying rack for parkas, boot liners and other winter clothes hung above the stove, suspended from crossbeams. The entire interior, logs and furniture, had been richly varnished.

Time for breakfast. Kathleen retrieved another bucket of snow, and melted it quickly on the propane stove. Soon we sat at our kitchen table, eating oatmeal, sipping tea, and toasting the last slices of Dave’s homemade bread on top of the wood stove – very comfortable. Getting a little too comfortable. We have work to do. Today's next priority is to establish camp procedures for getting water that’s already in liquid form, as melting snow takes too much time and too many refills of the bucket.

A long-handled broom with a hole already drilled through the wooden end hung on the cabin wall. Perfect. I rummaged through a green storage bin looking for woven nylon rope. I’m very fond of saying, “You can't have too much rope on a wilderness trip.” I cut out a 30-cm length, and burned both ends with a match to prevent unraveling. I then looped one end through the handle of our metal bucket, and poked the other end through the broom-handle hole. I now tied the two ends together with a sheet bend, an easy knot that, according to my old Boy Scout handbook, can be trusted to never work itself loose.

After grabbing an axe hanging on the outside wall in the enclosed porch, I strolled out into the crisp morning (still -19 degrees) down to the frozen edge of the outlet of Colville Lake. Bern had said that the ice was thin here, and often remained open for long periods during the winter. Standing at the outlet's margin, I eyed the ice cautiously. I slowly stepped out a few paces from shore, testing the surface before me by striking it with the wooden axe handle. I repeatedly glanced behind to confirm that no water was wicking up into my tracks. The ice seemed firm and solid. I dropped to my knees, to distribute my weight more evenly, and to protect my feet against a possible glancing blow of steel axe on slick ice.

I reached out as far as I could, and banged the axe on the ice. Within five minutes, liquid water gushed upward and slid across the ice, appearing almost black against the wonderfully pure white background. I extended the broom handle, and lowered the dangling bucket into the ‘well.’ I felt very satisfied, as I lifted the bucket back out onto the ice – a bucket heavy with slush and ice chips floating in immaculate, clean water.

I carried the water back up the hill, where Kathleen was already going through the bins scattered outside our cabin. Snow, wafting in from the south on a gentle breeze, swirled about her face as she studied and re-arranged the contents of each bin. Periodically Kathleen would look up and say, “OK, this one is ready, Michael,” and I would sled the re-packaged bin or pack along the ridge to the second cabin.

By mid-afternoon, all the food that we would need for the next few weeks, plus the clothes and equipment that we would be wearing and using on a daily basis, was organized in our cabin. Everything else had been put in storage in the second cabin.

This second cabin would also serve as our emergency accommodation. Bern had left seven pages of instructions, in which he said, “speaking of emergencies, I have put enough firewood in Cabin II for one day in case Cabin I (our cabin) got burned out.” Burning ourselves out would certainly be an emergency. We added some more wood to Bern’s pile, put some newspaper and kindling in the stove, and left Cabin II unlocked.

After dinner of spaghetti and tea, we turned our attention to the SSBx-11A radio, and the instructions for contacting Bern Will Brown. Bern’s notes indicted the following four frequencies:

2220 for Local Trappers;

3360 (unused);

4441 for the Yukon Trappers and Outfitters; and

5730 a seldom-used frequency that would be for Bern and me.

Bern’s instructions said that we should call at 7:00 pm. If we failed to make contact, we should then call every hour on the hour until we reached him. At 7:00 pm precisely, I set the frequency dial to 5730, pushed the transmission button, and called out my first message of the winter: “Hello, Colville Lake Lodge. This is Mike calling from the outpost. Are you there, Colville Lake Lodge?”

I released the button, waited for the response, but heard nothing but static. I repeated the process: “Hello, Colville Lake Lodge. This is Mike calling from the outpost. Are you there, Colville Lake Lodge?” Again, nothing but static. I tried three more times before giving up.

At 8:00 pm I tried five more times: “Hello, Colville Lake Lodge. This is Mike calling from the outpost. Are you there, Colville Lake Lodge?” Once again, static mocked our ears as we strained to hear a response from Bern.

I paced around the cabin’s interior. And pacing wasn’t easy. Our cabin is small. I could pace only 2 to 3 steps before having to turn around. I was agitated though, and pacing seemed to help. I hate relying on technology that doesn’t work. “I wonder if there’s something wrong with the radio or antenna, Kathleen? Bern knows that we will be calling. We should hear something.”

I turned the dial to 4441, the frequency of the Yukon Trappers, who just happened to be going through their daily ‘winter sched’ to make sure everyone living out in the bush was OK. It seemed there were about a dozen people giving each other updates on winter travel conditions, trapping success, the low price of fur, and their general well-being.

“At least we know that our radio can receive messages, Kathleen. It’s getting kind of late. I don’t really want to wait around until 9:00 pm to call again. Let’s go to bed and try tomorrow.”

The next morning I woke at 7:15 am, perhaps because of the cold. The fire had gone out, and the cabin was only +3 C (37 F). I re-started the fire and slumbered until after 10 o’clock. I then chopped a larger, more convenient hole in the ice, and dragged a bucket of water back up to the cabin.

The temperature, after 48 hours, remained unchanged at -19 degrees. Snow and ice, driven before the strong south wind, bit into any exposed skin. Blowing snow had drifted into all of our previous tracks.

The 7:00 pm attempt at radio contact with Bern again produced nothing but static riding in upon the southern winds. I felt quite frustrated. To be regimented by a daily and then an hourly schedule made me feel as though we were under house arrest. I didn’t come to Colville Lake to be monitored. I came to Colville Lake to escape regimentation.

The 8:00 pm contact also failed, although I again easily eavesdropped on the Yukon trappers, as they complained about low fur prices. I don’t know why Bern doesn’t try the 4441 frequency. The radio is producing the opposite effect for which it was intended. Instead of Bern knowing that we are fine, he will now be needlessly worried that something might have gone wrong. I very much resent this radio, and wish we didn’t have it.

The Yukon trappers had said that the northern lights were causing transmission problems. Maybe our signal is too weak for Bern to hear us. Maybe the batteries are too cold. I ran my fingers across the back of the radio, which did feel quite cold. The radio is a long way from the fire. Maybe it needs to be warmed up.

I retrieved a roll of aluminum foil from the cupboard. I then fastened a rectangular covering, open at the front, which looked just like a Baker tent. I placed a lighted candle inside, at the back of the radio, and waited for the results. By 8:45 the radio compartment housing the nine ‘D’ batteries felt warm to my touch. At 8:58 pm I sat before the radio, holding the transmitter hopefully, even expectantly, in my left hand.

Two minutes later I pushed the transmitter button and yelled out my tiresome phrase, “Hello, Colville Lake Lodge. This is Mike calling from the outpost. Are you there, Colville Lake Lodge?” I released the button, but heard nothing but a monotonic, irritating stream of static.

I stared disdainfully at the silent, metal box. I felt quite annoyed with the radio’s inanimate, malevolent stubbornness.

Just before noon the next day, we loaded our plastic toboggan with supplies and gear for our first trip out onto Colville Lake. To be safe we packed heavy down parkas for when we rested; spare woolen mitts and gauntlets in case the ones we wore became wet or lost; and spare mukluks and duffel socks should we happen to go through the ice or step into overflow. We laced up the lamp wick on our snowshoes and headed south, along the eastshore, into a persistent, chilling wind.

We continued up Colville Lake, accompanied by the musical ‘swoosh, swoosh, swoosh’ of our snowshoes. We rounded several points into our new, everlasting, grayish-white, frozen landscape. We poked at the ice almost constantly with a wooden broom handle, checking for overflow, and trying to determine if the ice was thick or thin. We have very limited experience walking on water, and Kathleen and I both felt uneasy. We were so all alone. What would we do if we actually broke through the ice?

After several km (couple of miles) of very slow travel through our unexplored world, Kathleen spotted cabins on a ridge on the far western bank.

“Shall we go see?” I asked.

“I don’t know, Michael. Do you think it’s safe to cross over in the middle of the lake?”

“I don’t know. How would I know?”

We stood and fidgeted, cooling off rapidly in the cold wind swirling over and around us.

“The caribou have crossed right near here. Their trail goes almost right to the cabins. If they can cross, the ice must be thick enough.”

This certainly made sense to us. Moreover, just a month ago, we had driven our 2200 kg van, loaded with gear, across the ice on the Peel and Mackenzie Rivers. Two weeks ago we had been hauling our sled down the Mackenzie at Inuvik. We should, by now, know logically that the ice must be thick enough. Nevertheless, we remained uneasy. We stepped out gingerly toward the centre of Colville Lake. We poked at the ice, veered toward the caribou trail, and headed toward the three cabins.

Just before reaching the western shore we noticed the telltale “stained” colour of water that had flowed over thin ice, where the lake’s current squeezed between shore and an island. Until now we had seen overflow only once before, in Inuvik. We congratulated ourselves for our caution, as we jabbed at the overflow. The broom handle easily – way too easily – penetrated and disappeared below the ice. We circled around the island, far away from the overflow, and struggled up a steep embankment. With every step we sank into deep drifts. Labouriously we lifted a snowshoe weighted down with snow, and then placed the next snowshoe forward and up the slope, only to sink again. This is not exactly what we had in mind.

After dinner, at 7:00 pm, we again failed to make contact with Bern on the SSBx-11A radio. We tried for nearly 30 minutes, but heard only the perpetual, irksome, high-pitched static. In disgust, I stepped outside to check the temperature, which read -43 degrees. Yowee! Above me spread a white mantle of northern lights, arching in wispy layers toward the northern horizon. Kathleen joined me on the south-facing knoll beneath the flagpole. The aurora borealis soared above our upturned heads. Rising like great columns of smoke from infinite campfires blazing below the southern horizon, the lights twirled, furled, folded and then fanned outward, until the infinite solar winds eventually hurled them beyond the northern limits of our vision. We stood transfixed for five minutes, until the penetrating cold drove us back to the warmth of our cabin.

At the next appointed hour of 8:00 o’clock I again dutifully tried to contact Bern. “Hello, Colville Lake Lodge. This is Mike calling from the outpost. Are you there, Colville Lake Lodge?”

I’m getting real tired of saying that. I tried for five minutes, with no response, other than the familiar static. I switched over to frequency 4441, and listened to each of the trappers recite in sequence their particular concerns and comments to their colleagues spread across the southern and central Yukon. Finally, Frank, coordinator of the nightly event, gave the usual invitation that I was waiting for: “Any other station wishing to call this winter sched can do so now.”

I quickly depressed the transmitting button, and shouted at the radio. “Colville Lake calling. Can you hear me?”

“I copy you loud and clear, Colville Lake,” Frank said. “What can I do for you?”

“I just wanted to see if anyone could hear me. I just wanted to confirm that my radio is working. I’ve been trying to contact Bern Will Brown at the south end of Colville Lake on 5370, with no success.”

“Well, Colville Lake. I hear you fine. I can’t help you with your party or that channel, though. Good luck.”

“Thanks,” I replied, only a little relieved. I turned off the radio. Where the heck is Bern, anyway? It was his idea to institute this daily schedule.

At 9:00 pm, I again tried the SSBx-11A radio, a stubborn and apparently useless piece of technology for which I was developing a very strong dislike. No response.

And then, at 10:00 p.m,

blammo! Like magic, Bern’s voice came floating out of the radio. “This is Colville Lake, go ahead Mike.”

I have to give Bern credit for his patience and perseverance – sitting silently by his radio, 40 km to the south, waiting four days for our message that he knew must surely come eventually. I asked him why it took four days. Had there been some problem?

“Well, Mike, I’ve been calling on the hour every night since you arrived, with no luck. These radios can be quite temperamental. Sometimes you can’t hear someone just across the street. Sometimes you can talk to a friend half way around the world using nothing more than a wet noodle for an antenna. It all depends on atmospheric conditions, the temperature, or even the northern lights. You never know, and there’s not much you can do about it.”

On the morning of February 5, I stood outside briefly at 6:15 am. Minus 42 C (-44 F), but still -4 C (+25 F) at sleeping height in the cabin. We had been letting the fire go out at night to conserve wood. Just after 9:00 a.m., I made the morning fire leisurely and comfortably. A few minutes later I lifted Kathleen down to the floor. We had recently moved all of our sleeping gear up to the third level of bunk beds, where it was warmer.

During breakfast we decided to spend the day snowshoeing north, down the small river below Colville Lake, toward Ketaniatue Lake, 6 km away. Our topographic map shows an obvious constriction in the middle of Ketaniatue Lake. We later learned that in the Slavey language,

Ketania means ‘narrows,’ and

tue means ‘lake.’

Blue skies greeted our northward advance as we cut across the outlet of Colville Lake to skirt a small island. Out in the open, away from the forest of spruce, the wind had sculpted the soft snow into small, rigid furrows, like the uniform ridges on a sandy beach swept by a gentle ocean. Jamie Bastedo, in his book

Going North, presents an essay about the research of Bill Pruitt, a renowned snow scientist. Pruitt reports that the Forest Eskimo of Northwest Alaska refer to these hardened snow formations as

upsik.

The ‘clack, clack, clack’ from our wooden snowshoes clicking across the furrowed

upsik was the only sound to disturb the frozen silence. No Ravens calling to each other across the valley– no Gray Jays whistling for hand outs. Silence dominated our physical world. Silence permeated our very existence. We followed a caribou trail down the centre of the river, trusting in the animals’ inherent ability to find ice strong enough to support their weight. Tracks of snowshoe hares and its silent predator, the lynx, crossed our trail. Both sets of tracks led east, and then disappeared into the willows along the river’s margin.

Half-a-kilometre ahead, the caribou trail veered right, along the edge of a light, yellow-gray discolouration. Water must be wicking into the snow from overflow. I poked at the overflow with my stick. An oily, black liquid oozed upward, and slid ominously across the ice toward our snowshoes. Kathleen and I both immediately jumped back, like cats startled by a bug in the grass. We were still very cautious in our new experience of walking on water. I would really hate to fall through the ice. I know that sounds obvious; but I would really hate it. I would like it even less if Kathleen fell through the ice. I worry most of the time about falling through the ice. Perhaps we will eventually become more confident.

In the afternoon the wind shifted to blow from the northwest, pulling a blanket of gray from the horizon down to the very tips of the spruce forest. Snow soon followed, and we returned to the cabin.

The next morning, we sat lingering by the fire, enjoying our oatmeal, sipping tea, and toasting bread on the wood stove. The morning sun streams through the south-facing window, and we bask in its light. We read. We reflect. As never before, I feel completely content.

We try our best to take pictures, but Kathleen says, and she's right, it's difficult at -40 (C & F). Kathleen tries to compose shots, and select the best locations, as she trudges back and forth from the outhouse. We usually take three shots, bracketing the reading booth on F stop up and one down. By then her hands and nose are freezing. About 5 minutes of picture taking is about all that is comfortable.Temperatures won't stay at -40 forever, we hope.

Minus 40 has a way of making a man feel like he needs more wood. We had paid Bern for 2 cords of wood to be left last fall. Snow had buried the wood, and we had no idea how much wood we had, or how much we would need. After breakfast I snowshoed about 1 km (0.5 miles) out to find 2 felled trees that Bern told us were still there from last September. I thoroughly enjoy working alone -- in silence – surrounded by the frozen forest.

Before we left Vancouver, I bought this bow saw. I didn't want the noise of a chain saw. I told the sales person where I was going and that I would also lake to buy a spare blade. He looked surprised. "You're going to be gone 5 months, and you can't get a replacement. They're only $5.00. Why don't you get two spares?" Good advice, I thought.

When I tire, I return home where Kathleen hands me a hot cup of chocolate and a grilled cheese sandwich. I rest, and then snowshoe back out to the forest for more wood to heat our cabin.

On February 8, Just before dusk, a group of caribou walked slowly toward our cabin from the south. They continued down their trail in mid-lake, seemingly at ease, until they reached the narrow constriction opposite our cabin. Through this gap the outlet flowed beneath shallow snow and thin, fragile ice. The herd broke into groups of 3-5 animals. As each smaller group burst through the gap, safely reaching the other side, every animal stopped to look back, seemingly checking on the security and progress of its companions.

On February 12, we spent an exhilarating afternoon snowshoeing 3 km (two miles) south, up Colville Lake, along the eastern shore. The sky hung heavenly blue above the spires of spruce, red bark fluorescing in the sun, branches festooned with rows of sparkling snow. A lone gray jay twittered in the background, then glided across a clearing with a smooth, undulating flight. Temperature comfortably warm at minus 29 C (-20 F).

We turned east onto the frozen streambed, between ridges that sheltered us from the quickening southwest wind. I felt so very lucky to be walking through a scene that, to me, can not be surpassed in beauty, tranquillity, and allure. The winding stream beckoned us ever onward to reveal hidden secrets around each bend. The black spires of the noble, serene forest reached upward into an azure sky bathed in sunlight, silence and the sublime cold that now seemed soothing, invigorating and inviting. This un-named valley came to be our favorite place, and we returned many times during the winter.

For Valentine’s Dinner, Kathleen made pizza, followed by butterscotch pudding for dessert. She was particularly proud of the pizza, which she said presented a great challenge because she had no oven. Kathleen is a resourceful, resilient person, and solved her pizza problem by using a heavy cast iron pan covered with tin foil. The pizza required only about 30 minutes to cook over a low heat. The bottom of the crust was crispy, but not burned. In addition to being a wonderful cook, Kathleen is also very modest. This time though, even she acknowledged that “the pizza was quite good!”

While Kathleen had been making the dinner, I strolled outside, telling her that I “just wanted to look around.” I collected some dried grasses on the south-facing knoll below the flagpole. I then strolled down to a small depression to harvest a few fluffy heads from last season’s cotton-grass. Returning along the snow trail, I picked up a few spruce cones. Back in the cabin I arranged them as a centrepiece for our Valentine’s Day table. Kathleen’s face beamed with surprise and happiness. I had to agree with her that I had indeed been very thoughtful.

Dining by candlelight, we planned our tasks and activities for the next day. Kathleen’s current plan for tomorrow is to experiment with some of the suggestions in the landscape photography book that I gave her for Christmas. She points out, however, that if something else comes up – even if that something else is just sipping tea and reading by the fire – then that’s what she’ll do. Kathleen and I are both enjoying this stress-free environment.

This is a canoe tripping site, so I thought you would like to see our canoe, as it waits patiently for break up, when we will paddle 4 weeks and 550 km (340 miles) down the Anderson River to Liverpool Bay on the Arctic Coast.

On February 17, we decided to spend the afternoon in the cabin, as the poor visibility seemed very uninviting. While writing in her journal, Kathleen happened to glance up the lake. “Michael, I think I see a light.”

“Where? Where would a light come from?”

“I don’t know, but it looks like a light, way up the lake. I can’t really tell with all that snow.”

I peered into the drifting, swirling white. “I don’t see anything.”

“I can’t see it now either. Must have just been an illusion.”

We both stared through the window.

“No, I think I see it again,” said Kathleen. “I’m going outside.”

I followed her out, and we both stared up the lake. There was no doubt about it now. Not just one light, but two lights, side-by-side, flickered far out on the lake. They seemed to be getting closer. Moments later we heard the unmistakable sound of ski-doos. Someone is coming! Who could it be?

Five minutes later, two ski-doos roared to a fuming stop just outside our cabin door. A man took off one mitt, and held out his hand. “Hello, we’ve come to see how you are doing out here. I’m Ron. These are my two boys, and this is their friend.”

Pretty darned exciting! At least, for us it was very darned exciting.

“Come in, come in. Have a chair by the fire. We don’t have enough chairs, but I can move those books off the bed. Make yourselves comfortable. Would you like some tea?”

Ron introduced himself as the regional community constable from Fort Good Hope. Ron travels by ski-doo from Fort Good Hope to Colville Lake, about 165 km (100 miles), once a month, checking up on people living in the bush.

Ron said he had been in town, and Bern suggested that he check up on us. Apparently I hadn’t completely convinced Bern during our radio conversations that things were going well. I can’t blame him for perhaps doubting me, though. After all, I am a city person, without any previous experience of living so isolated during a northern Canadian winter. Ron also brought some provisions from Bern and Margaret – a huge box of frozen fish, and another box overflowing with frozen caribou. I don’t know how we’re going to eat it all.

Ron sat at the table, slowly looking around the cabin, cupping the hot mug of tea in his hands. “Nice fire,” he said. “You got a lot of wood. I never been in here before.” Ron sipped and looked around. “Not too big. Easy to heat. Where’s all your food?”

“There’s a second cabin about 100 yards farther up the hill. You want to see what it’s like?” Ron nodded that he would.

A few minutes later Ron and the three boys sat down again, cradling tea mugs in their hands. “You seen any moose or caribou?” Ron asked.

“A lot of caribou. No moose though.”

“You have a gun?”

“Yeah. Here it is.” I handed Ron my Browning .308.

“Nice. Lever action.”

“It’s light. I can carry it easy.”

Ron continued: “Bern says that you plan to go to town sometime.

“Maybe,” I replied.

“How you gonna get to town. Do you have a ski-doo?”

“No. We don’t have a ski-doo. We had planned to go to town at the end of this month, with our wall tent and portable wood stove. But we’re beginning to think that the trip would take too long. It would be pretty hard to break trail around the perimeter of the lake.”

Ron again nodded and looked around. “Maybe you should wait until the weather gets a little warmer, and just go straight across the lake. You wouldn’t need snowshoes on the lake. You could make it in two days. You could take a light tent and just sleep out on the ice.”

“I like that idea, Ron. I think we might do that.”

Ron finished his tea, and stood up. “I don’t think I can tell you anything. You seem to be doing fine. Thanks for the tea. One of my boys lost his neck scarf. Pretty cold out there on the ski-doo. Do you have a spare scarf?”

Ron and the boys bundled up. “I’ll be back next month. See you then.” A few minutes later we could barely hear the sound of their engines, and then all went silent. Kathleen and I stepped back into the cabin, which now seemed very empty. I added more wood to the stove, while Kathleen prepared more tea.

During our 7:00 pm radio conversation, Bern said that his wife Margaret, and the two school teachers, Jo-Ellen Lyslo and Robert Lyslo, would be visiting on Sunday. Great news. We very much enjoyed today’s surprise visit by Ron, and look forward to receiving more visitors during the winter.

Bern & Margaret had sent us some rations with Ron-- a whole box of frozen fish and one of frozen caribou. I don't know how we can eat it all! The whiskey jacks loved eating the “sawdust” left after I sawed up some meat for dinner.

On Sunday, February 21, the temperature has remained above -20 C (-4 F), and what a difference that is from -40 C. We could actually visit the outhouse with privy without parka, hat, and gloves, as long as the wind isn't strong. Kathleen made a large pot of caribou stew in hopes that Margaret, Robert & Jo-Ellen would visit today; but because of poor weather in town they won't be coming until early March.

We have spent a lot of time sitting by the fire, drinking tea, and then making the necessary trips to the outhouse. This, as it turns out, has been a serious mistake. For some reason, perhaps because the lighting is becoming better, I glanced down the hole. Not surprisingly, it turns out, at these temperatures, that urine freezes almost instantly, and doesn't drain away. Frozen urine had already nearly completely filled up our outhouse. And we have only just begun the fourth week of February! What are we going to do now?

When we described this more ‘human’ aspect of life in the bush during our slide shows after we returned to Vancouver, the audiences always laugh. This anecdote is a sure-fire crowd-pleaser. Let me assure you, though, that this brought no laughter to us that cold February morning. We needed a functional outhouse, or so we thought. I happened to mention this ‘mistake’ to Bern during a radio conversation. I thought it was kind of amusing, even though problematical.

Bern said, “What did you do that for? No one urinates in the outhouse.”

Well, maybe no one who knows about these things urinates in the outhouse. But we didn’t know. From then on we never urinated in the outhouse. Instead, we extended a path a little beyond, into the forest. A closer-in urination post for Kathleen, and a farther spot for me. We needed to reserve space in our outhouse for more ‘significant’ bodily functions. We could also save outhouse space by walking to the native tent camp, on an island, about six km (four miles) south. We have been there twice already, and know about its brand new outhouse. The camp is vacant, and no one would mind. We enjoy taking snowshoe excursions, and the outhouse provides a useful destination for a three-hour round trip.

In her diary, Kathleen writes "It is definitely uncommonly beautiful here. This morning began with dense fog, which cleared around noon. After the last 2 days of snow the trees again have a white covering, and now after the fog a thick frost coats everything from mosquito screens around the porch to the deciduous, leafless branches. The sparkling white lake, the white spruce spires reaching into the deep, blue sky, and the delicately white-covered branches of the aspen trees make for a breathtaking scene. And all of it is ours to enjoy. How can we be so lucky?"

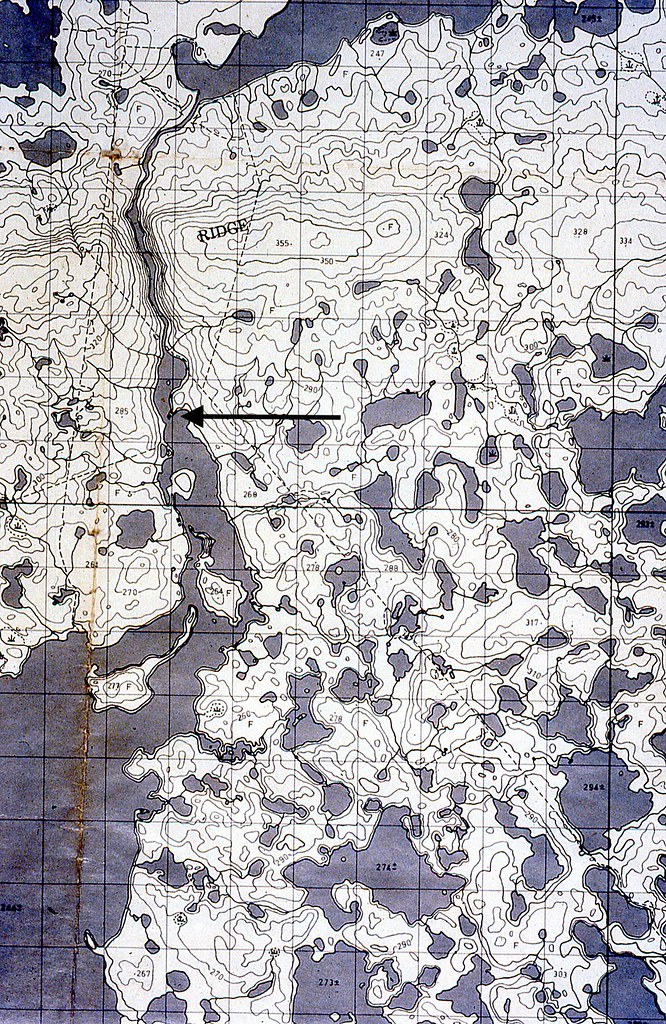

The arrow points to our cabin. The dotted line going north over the "Ridge" is a cut line leading about 5.5 km (a little over three miles) to Ketaniatue Lake. Kathleen and I put in snow shoe trails to the lake along the cut line, as well as down the river, which Bern calls the Ross River, leading to Ketaniatue Lake. We also put in a trail to the large island about 6 km (4 miles) south to the large island of the native tent camp.

On February 23, the day began overcast, as we headed down the river, to Ketaniatue Lake, shortly after 11:00 am. The sun emerged about 30 minutes later, bringing the snow-covered ridges into marvellous contrast with the dark sky above. Several sections of the river, up to 200 m (yards) long, now ran free and open. Areas that we had walked on only a few days ago were now flowing. Twice we had to leave the river corridor, and our previous path, to work our way through the bush. Twice my snowshoes became encased in ice because of wicking up from the slush below the snow. The lamp wick bindings had shredded apart by the time I returned from our 10 km, five-and-one-half hour trip. A successful day, as we finally reached Ketaniatue Lake via the river.

In addition to simply enjoying our stroll down and along the river, we had also been scouting out potential spots for setting up our wall tent. We found several good camping spots, with standing dead wood on both banks, just before the river empties into Ketaniatue Lake. Depending on the weather, we plan to return in a couple of days.

After dinner, I sat by the fire, enjoying the twilight descending around our cabin, and sipping at a full mug of hot orange juice. Back at home, in North Vancouver, I would most likely be sipping a glass of wine. In fact, Kathleen and I have wine with dinner virtually every night. We also often pour ourselves a glass of brandy before bed. It’s just what we do. It is our habit – our lifestyle.

For our winter sojourn, however, we have brought no alcohol. None whatsoever. We have left our drinking habits back in the city for three reasons. First, it would be impossible to bring enough wine and brandy to last for six months, particularly if we were to continue drinking on a daily basis. Secondly, it’s nice to break with old habits. We don’t really need to drink every day. It’s expensive and likely not good for our health. We likely drink every day at home simply because of routine. Here at our new Colville Lake home, we don’t miss alcohol at all. Alcohol is no longer part of our lifestyle. When no alcohol is available, it is easy to resist the lure of alcohol. When no alcohol is available, it is very simple to give up alcohol.

The third reason we didn’t bring any alcohol, and the most important reason for us, was that we didn’t want any alcohol on site. We expect to eventually have visitors from town. Although Colville Lake is officially a dry town, problem drinking does occur. When our town visitors ask us if we have any alcohol, we want to be able to honestly say, “No, we don’t have any alcohol.” We don’t want to contribute to the problem, and we don’t want to lie to people.

We spent the day organizing for our two-night camping trip at Ketaniatue Lake. There’s a heck of a lot to take. There are obvious items such as tent and guy ropes, wood stove, food, sleeping gear and clothing, including spare mukluks in case we step into overflow. We will also require many tools. We must have a hammer and nails to make a platform for the wood stove. A bow saw is necessary to cut down trees for firewood. Taking a spare saw blade is only prudent. We gotta have a machete to collect spruce boughs to lay across the tent entryway and sleeping platform, which would otherwise become slick sheets of ice from the heat of the stove. And certainly we need a small axe to limb trees and to clear the tent site. This is only a partial list of tools. There are also many necessary incidental items including water buckets, candles, aluminum foil, headlamps, pots and pans and a tea thermos. Our sled and toboggan will be fully loaded and heavy.

We remember how hard it was for me to drag out to Ron and Suzanne’s delta camp when we were in Inuvik. We should leave all superfluous items behind. We can’t afford to be fatigued when we reach camp, as much work will still need to be done. We need to travel as light as possible. The ice chisel is heavy at 1.5 kg. We probably won’t need it, as we expect to find thin ice, or even open water. We decide to combine our overnight cases – we don’t need to take two tubes of toothpaste. I don’t really need my razor, as I doubt that I will be shaving. Hey, every bit helps. Certainly we don’t need two cameras – shall we take my camera or Kathleen’s? Better pack the tripod though, to compose that special shot. On the other hand, the tripod is a bit cumbersome, and takes up a lot of room. Maybe we won’t need the tripod. Let’s leave it aside for now, and see how the packing goes in the morning.

We re-read our instructions for how to set the tent up, and for how to organize a winter camp. I would like to leave our cabin no later than 10:00 am. This gives us four hours to drag our gear down the river, to arrive at Ketaniatue Lake no later than 2:00 pm. We estimate it will take one hour to set the tent up, plus another 90 minutes to cut, haul, split and stack wood. This takes us to 4:30, leaving two more hours of daylight as a cushion should anything go wrong. We’ll see how it goes

We were ready to go at 11:00 am. – into a northwest wind at -18 degrees. Kathleen was responsible for the lead toboggan loaded with sleeping bags, pillows, ground sheet, tarp, therma-rests and down booties. Her toboggan also contained the down parkas, axe, maps, a shovel and the machete. My sled was stacked with the wood stove, canvass tent, vinyl tent fly, aluminum poles, my camera, the tripod (it truly is essential to capture well-composed images), water bucket, first aid kit and two white, plastic buckets containing kitchen gear, ropes and assorted tools. Kathleen set off as I raised the continuous leather towline over my head, and snugged it around my shoulders. I double-looped both arms into the line, and strained forward against the weight. Our loads dragged us down to the bottom of the hill, where we turned toward Ketaniatue Lake, 6 km down the Ross River, to the north. Comfortable weather for dragging at -18 C (about zero F).