- Joined

- Aug 21, 2018

- Messages

- 1,812

- Reaction score

- 4,603

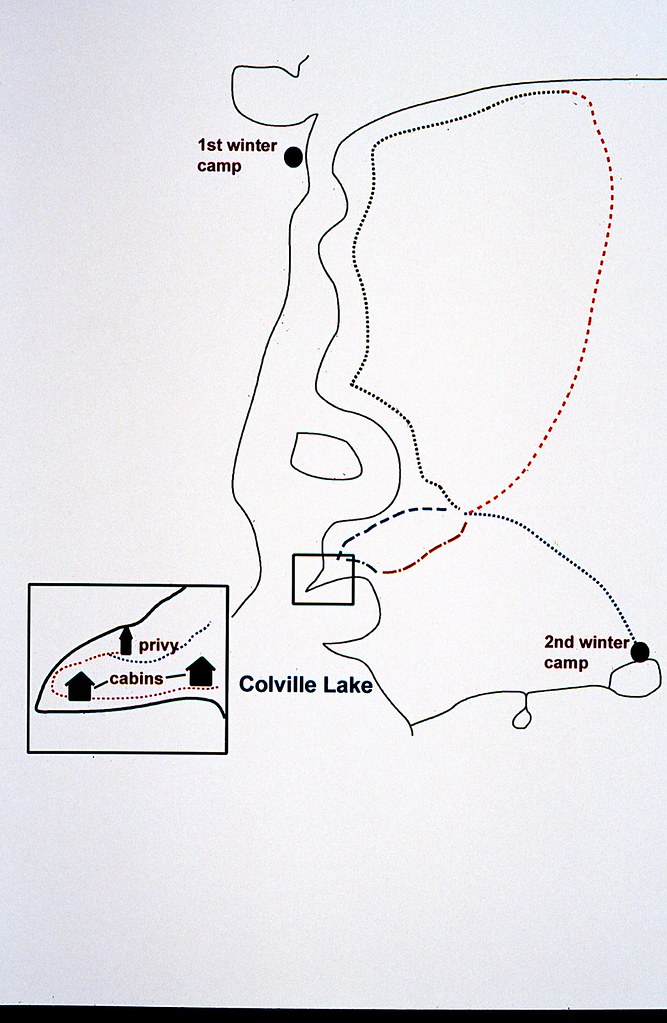

(Note: We had set out for our winter camp on Friday, February 26. One of the main reason I wanted this winter experience was to travel through the bush in winter. This was along-anticipated day for us. The following description is a bit long, and I thought it might be too much to present. But then I thought no one has to read it completely if they don't want to. There is no exam. Feel free to skim, or simply scroll through the words to look at the images. But I will present an edited summary of the longer description in case you are interested.)

The river had opened up even more since our trip out two days ago. Once, as we stood on an outside bank, an ice jam broke free just beneath our feet to muscle its way down river, shearing off snow and 15-cm (6-inch) thick ice as it eventually came to rest 200 m (yards) down stream. In general, though, we pulled our loads easily and without worry along the edge of the frozen river. We travelled mostly without speaking, lulled by the rhythmic ‘whump, whump, whump’ of our snowshoes sinking into soft, fluffy crystals. We walked in shared silence, heading down the frozen Ross River. The boreal forest stool passively, receptively, on both banks. No bird flew, no animal moved. Nothing disturbed our winter reverie. Only a few tracks appeared sporadically in the snow to suggest that any other life existed in our private, winter palace.

Through billowing snow we followed a caribou trail down the centre of the river, once again trusting the animals’ innate sense of ice strong enough to support the herd’s weight. Half-a-kilometre (quarter mile) later, the caribou trail angled toward the left bank, and skirted along a margin of yellow-green overflow oozing out from the centre of the river. We moved forward a few steps, when Kathleen suddenly stepped into overflow. She quickly retreated to dry snow, into which she buried her feet to wick away the moisture from her mukluks and snowshoes, which momentarily froze into the dry snow.

As Kathleen knocked away the snow and frozen slush, she said her feet seemed dry. No need to change into the spare socks and mukluks that we had packed on top of the gear, where they would be easily and quickly available. We now looked for another route around the overflow. We could see that the caribou tracks veered sharply toward the willows lining the left bank. Just at the river’s edge, the ice sloped upward at an angle of 20 degrees. Below this ice ramp we clearly heard the sound of water rushing past the outside bend.

“I don’t like this,” Kathleen said. “If there’s a gap between the ice and the river, then the ice might not be strong enough to support us.”

I picked up a stick and poked several times at the angled ramp of ice. The entire sheet, perhaps only 4-5 cm thick, wavered, cracked and buckled. “This doesn’t seem like a good way to go. Perhaps the caribou came this way before the river dropped so much.”

“Well,” Kathleen said, “we can’t get to the right bank because of the overflow, and now we can’t get up onto the left bank. We seem to be boxed in. Maybe we’ll have to go back a ways.”

“I don’t know. Maybe we don’t have to go back. Let’s go have another look at the overflow. We might be able to get through there.”

We walked back to the oozing overflow in the centre of the river, bringing my stick with me. “Just stand back a little bit, Kathleen, in case I need room to jump back quickly.”

I jabbed at the overflow, and the stick effortlessly sliced through the newly-formed ice only 2 cm thick. Water bubbled up, and slid sickeningly and blackly across the previously hardened overflow. We calmly, but intently, backed up in our snowshoe tracks, which offered the only known route to safety.

We returned along our previous path 100 m back up the Ross River, where I again tested the ice. Although the stick easily pierced through the overflow, no water seeped upward. The gurgle of the river was barely audible, suggesting only a thin gap between thicker ice and flowing water.

“What do you think?” I asked.

“How would I know? You’re out there poking with the stick. What do you think?”

“Well, I think we can cross over here. That would save us a lot of backtracking. But I can’t get that image out of my mind of Charles Martin Smith falling through the ice in that movie Never Cry Wolf.

“Well, you know, if you’re at all worried, Michael, we don’t have to cross here. We can always head back even more up-river.”

“Yeah, I know. But I think it is safe to cross here. Maybe though, we should cross one-at-a-time, so as not to concentrate our weight.”

“OK. But we don’t have to cross here, if you have any doubts.”

It seemed that Kathleen had some doubts.

“I’m feeling pretty confident, Kathleen. I’ll give it a try.”

I moved cautiously, jabbing and poking at the ice every few steps. I soon stood on the right bank, the inside bend, where shallower water had frozen all the way to the riverbed. I looked back toward Kathleen, who stood calmly in the centre of the Ross River, nearly enveloped by drifting, blowing snow.

“dang, you look beautiful out there, Kathleen. Just like Julie Christie in Dr. Zhivago. I think the ice is fine. Just go slowly. Make sure you don’t jump up and down too much.”

“Not funny. Here I come. Wait there for me.” Moments later we stood side-by-side, and continued our journey down the frozen Ross River toward Ketaniatue Lake.

Suddenly the sun burst through the snowy mist. The amorphous, nearly featureless, seemingly lifeless river corridor instantly awakened, as though to spring. Small coveys of Willow Ptarmigan, pure white save for their black tails, exploded from river-side copses. Whiskey Jacks swooped coyly out from the forest, twittering pleasingly as they begged for handouts. A lone Boreal Chickadee performed acrobatically for us, flitting from tree-top to tree-top, searching for over-wintering insects that slumbered, unsuspectingly, in their cocoons.

The Ross River now flowed between ridges that sheltered us from the persistent northwest wind. By mid-afternoon, the Ross River narrowed to 20 m, (yards) and ran nearly north/south, in a direct line with the prevailing winds. Winter gusts had sculpted and hardened the ice to create a surface as smooth and firm as a suburban sidewalk. Our snowshoes clattered happily as we pulled our loads easily on the frictionless crust.

We arrived at our intended camp at 2:45 pm, but needed nearly 4 hours to set up the tent, organize camp, and cut wood from two nearby dead spruce trees. We cleared an area of brush, and strung our tent between two live spruce trees. The sides of the tent were pulled taut with guy ropes tied to adjacent stumps, snags and saplings. I excavated a snow basin for the wood-burning stove while Kathleen used the machete to harvest spruce boughs for our floor of green.

I then placed some of the split wood around the stove, where it would dry during the night. This wood, which absorbs heat from the stove, will also help prevent melt-back of the cooking area that could cause the stove and stove pipes to shift or collapse. I stacked the rest of the split wood outside the tent door where it would be easily accessible during the night. Finally, I started the fire, and collected snow to melt for tea and drinking water. A difficult day for me physically, but thoroughly enjoyable. I’m finally experiencing what it means to camp in a frozen, winter, northern forest.

The tent quickly warmed to +25 C (77 F). While I rested in the heat, Kathleen leisurely prepared chili and cornbread bannock for dinner on top of the wood stove. We have now been at the north end of Colville Lake for nearly one month, and have seen only the RCMP who came specifically to visit us. Kathleen remarked how fortunate we are to live and travel in a landscape that is essentially ours to enjoy in whatever way we wish.

I wrote in my diary by candlelight with the stove purring and all the chores complete. I felt completely satiated with our chili dinner; but Kathleen is passing oatmeal chocolate chip cookies my way!

The temperature remained at -16 C (3 F) all last night. We allowed the fire to go out at 11:30 pm, partly out of concern about a tent fire, and partly because we had previously been warm in our wall tent in Inuvik, even when the temperature fell overnight to -26 C (-15 F). Minus 16 degrees sounded downright toasty by comparison. Nevertheless, Kathleen said she felt cold, beginning about 2:00 or 3:00 am.

I went to bed last night only reluctantly, as our tent looked so cute and charming by candlelight, with our winter gear silhouetted in the corners, and the stove keeping us warm. Even after Kathleen blew out the candles at 11:45 pm. I lay awake, enjoying the moment for another hour. The white cotton walls of our tent pass a great deal of light, such that it was still easy to see by the moonlight that periodically broke through the partial overcast.

The next day we took a short jaunt to Ketaniatue Lake today served two purposes, the first of which was to see some new country along the lake shore. Our second goal was to create a trail directly up against the right bank, just in case we can’t retrace our original path back across the river and the overflow tomorrow on Sunday.

In the afternoon we shored up the tent-stove platform with additional pieces of wood, and filled the melt back area around the stove with more snow. Stove shifting that separates the sections of pipe is a common cause of tent fires. I then resumed the tasks necessary to live comfortably through the winter night. I crossed back over the river to the right bank where this morning we had seen two, dead 4-m-tall (12-14 feet) spruce trees. I felled both, and sawed one of them into stove-sized lengths. I filled the toboggan with firewood and kindling, and returned to camp.

Kathleen stood in front of the tent, holding up our water buckets. She suggested that we try to get liquid water, rather than melting snow and slush. “After all,” she said, “there’s plenty of thin sections out there that should be easy to break through.”

Together we snowshoed happily 150 m (150 yards) along the edge of the river toward a narrow strip of discoloured snow. Here, on the outside bend, the water still ran quickly, and an insulating layer of snow kept the ice thin, even in very cold weather. Throughout the winter, the mass of ice developing in the centre of the river had been squeezing water up into this thin, weak zone of greyish slush. In a few minutes I axed a small hole, large enough for water to percolate up through the ice. We filled two water buckets with nearly ‘pure’ water that contained only a little slush.

Later that night, while Kathleen slept, I tended the fire and savoured tea. Periodically I stepped outside to a nearly completely cloudless sky. Stars filled our universe. Snow, two metres deep, reflected and diffused the pale light of the full moon throughout the surrounding, silent forest of spruce trees, which, like sentinels, stood guard over my winter sanctuary. A slight, gentle breeze wafted our smoke to the northwest. Maybe this southeast wind will bring warmer temperatures.

The night grew quickly clearer, losing its insulating cover of cloud. By 10:45 the temperature had dropped to -26 C (-15 F), dropping even lower to -29 C (-20 F) at midnight. I became too sleepy to stay up any longer. I placed a pot of water on the stove, damped down the air intake, crawled into my sleeping bag next to Kathleen’s, and quickly fell asleep. The stove continued to purr until the few remaining coals flickered out. The last vestige of heat then filtered through the canvass roof to disappear, wraith-like, into the arctic night. Cold encircled our tent, where Kathleen and I were turtled down, very deep inside our sleeping bags.

(Sorry about the black debris in the lower right. Don't want to take the time to rescan the slide!)

Shortly after 8:00 am, a Raven sounded the wake-up alarm. Time to get going. The smoldering logs in the stove had kept the pot of water on top in liquid form, even though another pot only 50 cm away on the ground had frozen solidly to the bottom. Outside, the slightly overcast morning had warmed to -19 degrees. Kathleen happily reported that she had slept comfortably all night.

The return trip to our cabin home was gloriously beautiful, with the sun shining brightly for the first time in many days. A light mist of ice crystals fell through the clear, clean air. As the crystals settled on the surface of the snow, they sparkled like millions of individual stars. We often stopped, not only to rest, but also to enjoy and to admire the spectacle at our feet, glistening in the sunlight.

When we first travelled along this river two weeks ago, very little open water existed. We had snowshoed easily, and without concern. Now, however, the river had carved out long stretches of open water, even more than had existed only two days ago. Everything seemed to be in transition and unstable. We no longer trusted our original route, and often left the river completely to break new trail along the edge of the bank. Once, just as Kathleen had stepped off an ice shelf into the trees, the ledge gave way beneath her toboggan, and fell away into the river. Fortunately we didn’t lose any gear. Even more fortunately, we didn’t lose Kathleen.

The sun was actually warming my face when we reached the cabin in mid-afternoon, somewhat tired, but very satisfied. It felt like coming home. It also seemed as though a new portion of the winter had begun. The outside thermometer read -11 C (+12 F). I hesitate to say that spring was near, but icicles hung and dripped from the south-facing eave, and the ice in The Narrows lay decaying before us. Maybe warm weather is not too distant into our future.

We unlocked the door and removed the window shutters. Sun streamed and sparkled throughout the cabin as never before. We started the fire and settled into a tranquil evening of reading, writing, sipping tea, pumping the Coleman lantern, popping a bowl of popcorn, and playing cribbage.

After breakfast, on March 3, we headed back up the cut line over the "Ridge" to break more snow trail to Ketaniatue Lake. Above Colville Lake, to our south, a spectacular parhelion encircled the sun. Bright sunlight shone down upon us as we showshoed through open stands of spruce draped with sparkling mounds of snow.

Even though our breath condensed into frost as we hiked, we felt completely warm.

In slightly less than two hours we had packed an additional 1.5 km (1 mile) of trail, and finally stood on Colville Ridge, at the height of land, gazing down upon Ketaniatue Lake 120 m below 2 km (1.2 miles) to the north. The hardest, uphill section of our trail has now been completed.

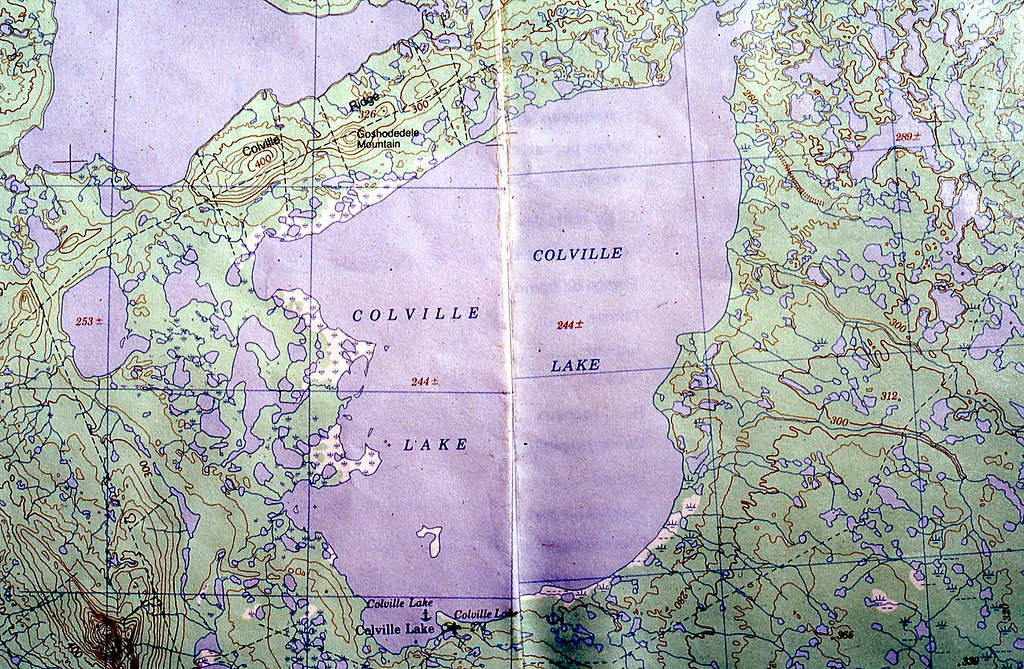

Kathleen and I stood together, content with our work. We silently faced into the cold wind that streamed toward us from somewhere out over the Arctic Ocean, 500 km (300 miles) to the north. At that moment, during the depth of winter, it is very likely that Kathleen and I were the last two people on the North American continent, in a 350-km-wide (215 miles) swath between Tuktoyaktuk and Paulatuk, in all of that isolated vastness north to the polar sea. Behind us, 45 km (28 miles) to the south, fewer than 100 people lived in Colville Lake. Only 640 people lived in Fort Good Hope, the next closest community, 160 km (100 miles) to the southwest, as the Raven flies. The nearest paved road, the end of the Dempster Highway at Inuvik, was 350 km (215 miles) to the northwest. The next closest all-weather road, at Wrigley on the Mackenzie River, ended 500 km due south.

We were truly alone – alone as we can be in today’s modern world.

On March 7 the temperature fell to -42 C (-43.5 F), and I began to wonder how much wood we actually had buried beneath the tarp just below the cabin.

Despite the cold weather, every day brings pure exhileration of gliding along our own snowshoe trails across frozen Colville Lake. It is as though the world has been newly created, and Kathleen and I are its first and only inhabitants.

Since arriving here on January 31[SUP]st[/SUP] we have seen only 4 people, the RCMP party, for a couple of hours.We are the only people in the country and we go at will or whim wherever we want. We have traveled north along the river, on the overland route, and south up Colville Lake. Our trails in the snow mark our passing. We see no one, except for the animals. This is truly our place. There aren't many places in the world a person has such freedom.

To provide some regimen to our lives, we have decreed that Friday is bath day, and that Saturday is laundry day. Doing laundry without power differs considerably from doing laundry at home. Doing laundry in North Vancouver is almost like an afterthought. Put the clothes in the washer, and then go away to do some gardening for half an hour or so. When the washer stops, transfer the clothes to the dryer. Turn on the dryer and then go away to enjoy a toasted bagel for lunch. Come back in half an hour or so to put away clean, fresh clothes. Get on with the rest of your day.

Here at the cabin, without electricity or running water, laundry is the rest of our day – laundry is our whole day. And it’s not because we have so many clothes to wash. In fact, we have very few clothes to wash, as we often wear the same clothes throughout the week. The laundry usually includes only two pairs of long wool underwear, two pairs of wool socks, plus 3 to 5 pairs of ‘regular’ underwear. Without power, however, laundry poses a formidable challenge to those of us accustomed to the comforts of city life.

To begin the process, I need to bring up eight buckets of water from the lake, two at a time. Kathleen heats the buckets on the propane stove and dumps the hot water into a larger metal basin. The clothes then soak for a while, until Kathleen washes them the very old-fashioned way, by rubbing and agitating them with her hands. We don’t even have a rock to pound them with. In Vancouver, we often go to antique and second-hand stores looking for interesting furnishings. We commonly have seen old washboards sitting idly on corner shelves. We then remark, with respect, how hard it must have been to wash clothes using just a washboard. How much we wish we had a washboard now. In all the readings we have done about the ‘how-to’ and romance of isolated cabin life in the bush, no one ever mentions the mundane task of doing laundry. No one ever mentions how useful it would be to take a simple item like a washboard. No one ever mentions how much this simple washboard could improve one’s life.

After the washing is done, I need to take out eight buckets of gray water, two at a time, and dump them, about 20 metres (yards) behind the cabin, over the hillside. I can’t just toss the used water outside the door, which would be much easier for me. Water is heavy, and difficult to carry very far. Water chucked outside the door, though, would instantly turn our pathway into a winter-long sheet of ice. The pathway to the outhouse, compact and slick from constant use, is already far too slippery. The path takes us over a little rise at the corner of the cabin, where we can read the thermometer hanging on the outside wall. Heading back down the slope has been particularly risky. Kathleen and I have fallen many times – probably twenty times each. Like a gunslinger’s belt, we should be carving notches into the wall to record the carnage. It’s getting to the point where we expect to careen down the hill, and we are becoming skilled at falling gracefully. Perhaps we should have planned a better route to the outhouse, or perhaps we should line the path with spruce boughs.

After dumping the gray water, I then need to bring eight more buckets up the hill, two at time. Kathleen heats the buckets on the propane stove and dumps the hot water into the metal basin. The clothes then soak for a while, until Kathleen wrings them out the very old-fashioned way, by twisting them with her hands. Kathleen says that the item she misses most from our home in Vancouver is the washing machine. More specifically, she misses the spin cycle of the washing machine. It takes a very long time of twisting and resting, and re-twisting, and flexing of tired wrists, and twisting again to wring enough water out of the clothes so that they are ready to hang.

We remember those long ago days of the 1950s, when our parents and grandparents owned ringer-washers – washing machines with a mechanical wringer mounted on the side. One still occasionally sees these machines at second-hand stores. How simple it would have been for us to have brought an old mechanical wringer. In all the readings we have done about the ‘how-to’ and romance of isolated cabin life in the bush, no one ever mentions the mundane task of doing laundry. No one ever mentions how useful it would be to take a simple item like a mechanical wringer. No one ever mentions how much this simple wringer could improve one’s life.

After the rinsing and wringing, I take out eight buckets of gray water, two at a time, and dump them, about 20 metres (yards) behind the cabin, over the hillside. We are now ready to hang the clothes.

When we first did laundry at the cabin, we hung the clothes on drying racks strung from the ceiling. This seemed logical, but was very inconvenient. First, the racks were small, and sometimes could not accommodate all of our clothes at once. Secondly, we quickly grew tired of walking into and between wet clothes for the rest of the day. So last week I packed in a path called Laundry Lane, at the end of which I strung a clothesline between two trees so that we could dry the clothes outside.

We hadread that even in the coldest temperatures, laundry would dry if the wind were blowing. The strong southeast wind from yesterday persisted, and we decided to hang our laundry outside, hoping for the magic of sublimation, whereby ice turns to a gas (vapor) without first passing through the liquid stage. Such a miracle would leave our dry clothes fluttering happily at the end of the day. I loaded up our laundry basket, grabbed my can of clothespins, and trudged out back to the clothesline. I picked up the first wool sock, which had frozen solid, and stood rigidly upright when I held it by the toe. I pinned it to the line, and reached for the next sock. It too was frozen solid. In fact, all the clothes had frozen solid.

Now, as you might suspect, pinning clothes to a line requires dexterity. Pinning clothes can not be done while wearing bulky mitts. Pinning clothes to a line requires fingers – fingers that quickly become numb and useless when exposed to wind and to frozen underwear, even at a relatively warm -6 C (+21 F). After a few minutes I retreated to the cabin to thaw my fingers. Eventually though, after a few trips out to pin, and a few trips back to thaw, all the clothes were hanging from the line. I sat down at the table to enjoy a mug of tea. The laundry seems to be under control.

Unfortunately the wind died a few hours after pinning our clothes to the line. Even nine hours later, all laundry except the pillow cases remained stiff as that proverbial board. Maybe we’ll have better success next time. Any way, laundry day was now over. In all the readings we had done about the “how to” and romance of isolated cabin life in the bush, no one ever mentioned how difficult laundry day would be. Then again, no one ever cautioned us against urinating in the outhouse, either.

On March 19, It now seems that perhaps we won’t need to cut much more wood. Today brought a strong southwest wind (30 km/hour; 20 miles/hour), and afternoon temperatures of minus 12 C (+10 F). We sit comfortably warm in the cabin as much as a metre (three feet) away from the stove. The ice above the narrows is slumping in a large semi-circle nearly from shore-to-shore. The days are getting longer. The sun is definitely warm. The weather report on CBC indicates plus temperatures (above 32 F) for many of the southern NWT places such as Hay River, Fort Smith. Even the western Arctic Coast temperatures are getting up in the minus teens (five or so F). It is almost 5:00 p.m., but the sun is still high in the sky.

The river had opened up even more since our trip out two days ago. Once, as we stood on an outside bank, an ice jam broke free just beneath our feet to muscle its way down river, shearing off snow and 15-cm (6-inch) thick ice as it eventually came to rest 200 m (yards) down stream. In general, though, we pulled our loads easily and without worry along the edge of the frozen river. We travelled mostly without speaking, lulled by the rhythmic ‘whump, whump, whump’ of our snowshoes sinking into soft, fluffy crystals. We walked in shared silence, heading down the frozen Ross River. The boreal forest stool passively, receptively, on both banks. No bird flew, no animal moved. Nothing disturbed our winter reverie. Only a few tracks appeared sporadically in the snow to suggest that any other life existed in our private, winter palace.

Through billowing snow we followed a caribou trail down the centre of the river, once again trusting the animals’ innate sense of ice strong enough to support the herd’s weight. Half-a-kilometre (quarter mile) later, the caribou trail angled toward the left bank, and skirted along a margin of yellow-green overflow oozing out from the centre of the river. We moved forward a few steps, when Kathleen suddenly stepped into overflow. She quickly retreated to dry snow, into which she buried her feet to wick away the moisture from her mukluks and snowshoes, which momentarily froze into the dry snow.

As Kathleen knocked away the snow and frozen slush, she said her feet seemed dry. No need to change into the spare socks and mukluks that we had packed on top of the gear, where they would be easily and quickly available. We now looked for another route around the overflow. We could see that the caribou tracks veered sharply toward the willows lining the left bank. Just at the river’s edge, the ice sloped upward at an angle of 20 degrees. Below this ice ramp we clearly heard the sound of water rushing past the outside bend.

“I don’t like this,” Kathleen said. “If there’s a gap between the ice and the river, then the ice might not be strong enough to support us.”

I picked up a stick and poked several times at the angled ramp of ice. The entire sheet, perhaps only 4-5 cm thick, wavered, cracked and buckled. “This doesn’t seem like a good way to go. Perhaps the caribou came this way before the river dropped so much.”

“Well,” Kathleen said, “we can’t get to the right bank because of the overflow, and now we can’t get up onto the left bank. We seem to be boxed in. Maybe we’ll have to go back a ways.”

“I don’t know. Maybe we don’t have to go back. Let’s go have another look at the overflow. We might be able to get through there.”

We walked back to the oozing overflow in the centre of the river, bringing my stick with me. “Just stand back a little bit, Kathleen, in case I need room to jump back quickly.”

I jabbed at the overflow, and the stick effortlessly sliced through the newly-formed ice only 2 cm thick. Water bubbled up, and slid sickeningly and blackly across the previously hardened overflow. We calmly, but intently, backed up in our snowshoe tracks, which offered the only known route to safety.

We returned along our previous path 100 m back up the Ross River, where I again tested the ice. Although the stick easily pierced through the overflow, no water seeped upward. The gurgle of the river was barely audible, suggesting only a thin gap between thicker ice and flowing water.

“What do you think?” I asked.

“How would I know? You’re out there poking with the stick. What do you think?”

“Well, I think we can cross over here. That would save us a lot of backtracking. But I can’t get that image out of my mind of Charles Martin Smith falling through the ice in that movie Never Cry Wolf.

“Well, you know, if you’re at all worried, Michael, we don’t have to cross here. We can always head back even more up-river.”

“Yeah, I know. But I think it is safe to cross here. Maybe though, we should cross one-at-a-time, so as not to concentrate our weight.”

“OK. But we don’t have to cross here, if you have any doubts.”

It seemed that Kathleen had some doubts.

“I’m feeling pretty confident, Kathleen. I’ll give it a try.”

I moved cautiously, jabbing and poking at the ice every few steps. I soon stood on the right bank, the inside bend, where shallower water had frozen all the way to the riverbed. I looked back toward Kathleen, who stood calmly in the centre of the Ross River, nearly enveloped by drifting, blowing snow.

“dang, you look beautiful out there, Kathleen. Just like Julie Christie in Dr. Zhivago. I think the ice is fine. Just go slowly. Make sure you don’t jump up and down too much.”

“Not funny. Here I come. Wait there for me.” Moments later we stood side-by-side, and continued our journey down the frozen Ross River toward Ketaniatue Lake.

Suddenly the sun burst through the snowy mist. The amorphous, nearly featureless, seemingly lifeless river corridor instantly awakened, as though to spring. Small coveys of Willow Ptarmigan, pure white save for their black tails, exploded from river-side copses. Whiskey Jacks swooped coyly out from the forest, twittering pleasingly as they begged for handouts. A lone Boreal Chickadee performed acrobatically for us, flitting from tree-top to tree-top, searching for over-wintering insects that slumbered, unsuspectingly, in their cocoons.

The Ross River now flowed between ridges that sheltered us from the persistent northwest wind. By mid-afternoon, the Ross River narrowed to 20 m, (yards) and ran nearly north/south, in a direct line with the prevailing winds. Winter gusts had sculpted and hardened the ice to create a surface as smooth and firm as a suburban sidewalk. Our snowshoes clattered happily as we pulled our loads easily on the frictionless crust.

We arrived at our intended camp at 2:45 pm, but needed nearly 4 hours to set up the tent, organize camp, and cut wood from two nearby dead spruce trees. We cleared an area of brush, and strung our tent between two live spruce trees. The sides of the tent were pulled taut with guy ropes tied to adjacent stumps, snags and saplings. I excavated a snow basin for the wood-burning stove while Kathleen used the machete to harvest spruce boughs for our floor of green.

I then placed some of the split wood around the stove, where it would dry during the night. This wood, which absorbs heat from the stove, will also help prevent melt-back of the cooking area that could cause the stove and stove pipes to shift or collapse. I stacked the rest of the split wood outside the tent door where it would be easily accessible during the night. Finally, I started the fire, and collected snow to melt for tea and drinking water. A difficult day for me physically, but thoroughly enjoyable. I’m finally experiencing what it means to camp in a frozen, winter, northern forest.

The tent quickly warmed to +25 C (77 F). While I rested in the heat, Kathleen leisurely prepared chili and cornbread bannock for dinner on top of the wood stove. We have now been at the north end of Colville Lake for nearly one month, and have seen only the RCMP who came specifically to visit us. Kathleen remarked how fortunate we are to live and travel in a landscape that is essentially ours to enjoy in whatever way we wish.

I wrote in my diary by candlelight with the stove purring and all the chores complete. I felt completely satiated with our chili dinner; but Kathleen is passing oatmeal chocolate chip cookies my way!

The temperature remained at -16 C (3 F) all last night. We allowed the fire to go out at 11:30 pm, partly out of concern about a tent fire, and partly because we had previously been warm in our wall tent in Inuvik, even when the temperature fell overnight to -26 C (-15 F). Minus 16 degrees sounded downright toasty by comparison. Nevertheless, Kathleen said she felt cold, beginning about 2:00 or 3:00 am.

I went to bed last night only reluctantly, as our tent looked so cute and charming by candlelight, with our winter gear silhouetted in the corners, and the stove keeping us warm. Even after Kathleen blew out the candles at 11:45 pm. I lay awake, enjoying the moment for another hour. The white cotton walls of our tent pass a great deal of light, such that it was still easy to see by the moonlight that periodically broke through the partial overcast.

The next day we took a short jaunt to Ketaniatue Lake today served two purposes, the first of which was to see some new country along the lake shore. Our second goal was to create a trail directly up against the right bank, just in case we can’t retrace our original path back across the river and the overflow tomorrow on Sunday.

In the afternoon we shored up the tent-stove platform with additional pieces of wood, and filled the melt back area around the stove with more snow. Stove shifting that separates the sections of pipe is a common cause of tent fires. I then resumed the tasks necessary to live comfortably through the winter night. I crossed back over the river to the right bank where this morning we had seen two, dead 4-m-tall (12-14 feet) spruce trees. I felled both, and sawed one of them into stove-sized lengths. I filled the toboggan with firewood and kindling, and returned to camp.

Kathleen stood in front of the tent, holding up our water buckets. She suggested that we try to get liquid water, rather than melting snow and slush. “After all,” she said, “there’s plenty of thin sections out there that should be easy to break through.”

Together we snowshoed happily 150 m (150 yards) along the edge of the river toward a narrow strip of discoloured snow. Here, on the outside bend, the water still ran quickly, and an insulating layer of snow kept the ice thin, even in very cold weather. Throughout the winter, the mass of ice developing in the centre of the river had been squeezing water up into this thin, weak zone of greyish slush. In a few minutes I axed a small hole, large enough for water to percolate up through the ice. We filled two water buckets with nearly ‘pure’ water that contained only a little slush.

Later that night, while Kathleen slept, I tended the fire and savoured tea. Periodically I stepped outside to a nearly completely cloudless sky. Stars filled our universe. Snow, two metres deep, reflected and diffused the pale light of the full moon throughout the surrounding, silent forest of spruce trees, which, like sentinels, stood guard over my winter sanctuary. A slight, gentle breeze wafted our smoke to the northwest. Maybe this southeast wind will bring warmer temperatures.

The night grew quickly clearer, losing its insulating cover of cloud. By 10:45 the temperature had dropped to -26 C (-15 F), dropping even lower to -29 C (-20 F) at midnight. I became too sleepy to stay up any longer. I placed a pot of water on the stove, damped down the air intake, crawled into my sleeping bag next to Kathleen’s, and quickly fell asleep. The stove continued to purr until the few remaining coals flickered out. The last vestige of heat then filtered through the canvass roof to disappear, wraith-like, into the arctic night. Cold encircled our tent, where Kathleen and I were turtled down, very deep inside our sleeping bags.

(Sorry about the black debris in the lower right. Don't want to take the time to rescan the slide!)

Shortly after 8:00 am, a Raven sounded the wake-up alarm. Time to get going. The smoldering logs in the stove had kept the pot of water on top in liquid form, even though another pot only 50 cm away on the ground had frozen solidly to the bottom. Outside, the slightly overcast morning had warmed to -19 degrees. Kathleen happily reported that she had slept comfortably all night.

The return trip to our cabin home was gloriously beautiful, with the sun shining brightly for the first time in many days. A light mist of ice crystals fell through the clear, clean air. As the crystals settled on the surface of the snow, they sparkled like millions of individual stars. We often stopped, not only to rest, but also to enjoy and to admire the spectacle at our feet, glistening in the sunlight.

When we first travelled along this river two weeks ago, very little open water existed. We had snowshoed easily, and without concern. Now, however, the river had carved out long stretches of open water, even more than had existed only two days ago. Everything seemed to be in transition and unstable. We no longer trusted our original route, and often left the river completely to break new trail along the edge of the bank. Once, just as Kathleen had stepped off an ice shelf into the trees, the ledge gave way beneath her toboggan, and fell away into the river. Fortunately we didn’t lose any gear. Even more fortunately, we didn’t lose Kathleen.

The sun was actually warming my face when we reached the cabin in mid-afternoon, somewhat tired, but very satisfied. It felt like coming home. It also seemed as though a new portion of the winter had begun. The outside thermometer read -11 C (+12 F). I hesitate to say that spring was near, but icicles hung and dripped from the south-facing eave, and the ice in The Narrows lay decaying before us. Maybe warm weather is not too distant into our future.

We unlocked the door and removed the window shutters. Sun streamed and sparkled throughout the cabin as never before. We started the fire and settled into a tranquil evening of reading, writing, sipping tea, pumping the Coleman lantern, popping a bowl of popcorn, and playing cribbage.

After breakfast, on March 3, we headed back up the cut line over the "Ridge" to break more snow trail to Ketaniatue Lake. Above Colville Lake, to our south, a spectacular parhelion encircled the sun. Bright sunlight shone down upon us as we showshoed through open stands of spruce draped with sparkling mounds of snow.

Even though our breath condensed into frost as we hiked, we felt completely warm.

In slightly less than two hours we had packed an additional 1.5 km (1 mile) of trail, and finally stood on Colville Ridge, at the height of land, gazing down upon Ketaniatue Lake 120 m below 2 km (1.2 miles) to the north. The hardest, uphill section of our trail has now been completed.

Kathleen and I stood together, content with our work. We silently faced into the cold wind that streamed toward us from somewhere out over the Arctic Ocean, 500 km (300 miles) to the north. At that moment, during the depth of winter, it is very likely that Kathleen and I were the last two people on the North American continent, in a 350-km-wide (215 miles) swath between Tuktoyaktuk and Paulatuk, in all of that isolated vastness north to the polar sea. Behind us, 45 km (28 miles) to the south, fewer than 100 people lived in Colville Lake. Only 640 people lived in Fort Good Hope, the next closest community, 160 km (100 miles) to the southwest, as the Raven flies. The nearest paved road, the end of the Dempster Highway at Inuvik, was 350 km (215 miles) to the northwest. The next closest all-weather road, at Wrigley on the Mackenzie River, ended 500 km due south.

We were truly alone – alone as we can be in today’s modern world.

On March 7 the temperature fell to -42 C (-43.5 F), and I began to wonder how much wood we actually had buried beneath the tarp just below the cabin.

Despite the cold weather, every day brings pure exhileration of gliding along our own snowshoe trails across frozen Colville Lake. It is as though the world has been newly created, and Kathleen and I are its first and only inhabitants.

Since arriving here on January 31[SUP]st[/SUP] we have seen only 4 people, the RCMP party, for a couple of hours.We are the only people in the country and we go at will or whim wherever we want. We have traveled north along the river, on the overland route, and south up Colville Lake. Our trails in the snow mark our passing. We see no one, except for the animals. This is truly our place. There aren't many places in the world a person has such freedom.

To provide some regimen to our lives, we have decreed that Friday is bath day, and that Saturday is laundry day. Doing laundry without power differs considerably from doing laundry at home. Doing laundry in North Vancouver is almost like an afterthought. Put the clothes in the washer, and then go away to do some gardening for half an hour or so. When the washer stops, transfer the clothes to the dryer. Turn on the dryer and then go away to enjoy a toasted bagel for lunch. Come back in half an hour or so to put away clean, fresh clothes. Get on with the rest of your day.

Here at the cabin, without electricity or running water, laundry is the rest of our day – laundry is our whole day. And it’s not because we have so many clothes to wash. In fact, we have very few clothes to wash, as we often wear the same clothes throughout the week. The laundry usually includes only two pairs of long wool underwear, two pairs of wool socks, plus 3 to 5 pairs of ‘regular’ underwear. Without power, however, laundry poses a formidable challenge to those of us accustomed to the comforts of city life.

To begin the process, I need to bring up eight buckets of water from the lake, two at a time. Kathleen heats the buckets on the propane stove and dumps the hot water into a larger metal basin. The clothes then soak for a while, until Kathleen washes them the very old-fashioned way, by rubbing and agitating them with her hands. We don’t even have a rock to pound them with. In Vancouver, we often go to antique and second-hand stores looking for interesting furnishings. We commonly have seen old washboards sitting idly on corner shelves. We then remark, with respect, how hard it must have been to wash clothes using just a washboard. How much we wish we had a washboard now. In all the readings we have done about the ‘how-to’ and romance of isolated cabin life in the bush, no one ever mentions the mundane task of doing laundry. No one ever mentions how useful it would be to take a simple item like a washboard. No one ever mentions how much this simple washboard could improve one’s life.

After the washing is done, I need to take out eight buckets of gray water, two at a time, and dump them, about 20 metres (yards) behind the cabin, over the hillside. I can’t just toss the used water outside the door, which would be much easier for me. Water is heavy, and difficult to carry very far. Water chucked outside the door, though, would instantly turn our pathway into a winter-long sheet of ice. The pathway to the outhouse, compact and slick from constant use, is already far too slippery. The path takes us over a little rise at the corner of the cabin, where we can read the thermometer hanging on the outside wall. Heading back down the slope has been particularly risky. Kathleen and I have fallen many times – probably twenty times each. Like a gunslinger’s belt, we should be carving notches into the wall to record the carnage. It’s getting to the point where we expect to careen down the hill, and we are becoming skilled at falling gracefully. Perhaps we should have planned a better route to the outhouse, or perhaps we should line the path with spruce boughs.

After dumping the gray water, I then need to bring eight more buckets up the hill, two at time. Kathleen heats the buckets on the propane stove and dumps the hot water into the metal basin. The clothes then soak for a while, until Kathleen wrings them out the very old-fashioned way, by twisting them with her hands. Kathleen says that the item she misses most from our home in Vancouver is the washing machine. More specifically, she misses the spin cycle of the washing machine. It takes a very long time of twisting and resting, and re-twisting, and flexing of tired wrists, and twisting again to wring enough water out of the clothes so that they are ready to hang.

We remember those long ago days of the 1950s, when our parents and grandparents owned ringer-washers – washing machines with a mechanical wringer mounted on the side. One still occasionally sees these machines at second-hand stores. How simple it would have been for us to have brought an old mechanical wringer. In all the readings we have done about the ‘how-to’ and romance of isolated cabin life in the bush, no one ever mentions the mundane task of doing laundry. No one ever mentions how useful it would be to take a simple item like a mechanical wringer. No one ever mentions how much this simple wringer could improve one’s life.

After the rinsing and wringing, I take out eight buckets of gray water, two at a time, and dump them, about 20 metres (yards) behind the cabin, over the hillside. We are now ready to hang the clothes.

When we first did laundry at the cabin, we hung the clothes on drying racks strung from the ceiling. This seemed logical, but was very inconvenient. First, the racks were small, and sometimes could not accommodate all of our clothes at once. Secondly, we quickly grew tired of walking into and between wet clothes for the rest of the day. So last week I packed in a path called Laundry Lane, at the end of which I strung a clothesline between two trees so that we could dry the clothes outside.

We hadread that even in the coldest temperatures, laundry would dry if the wind were blowing. The strong southeast wind from yesterday persisted, and we decided to hang our laundry outside, hoping for the magic of sublimation, whereby ice turns to a gas (vapor) without first passing through the liquid stage. Such a miracle would leave our dry clothes fluttering happily at the end of the day. I loaded up our laundry basket, grabbed my can of clothespins, and trudged out back to the clothesline. I picked up the first wool sock, which had frozen solid, and stood rigidly upright when I held it by the toe. I pinned it to the line, and reached for the next sock. It too was frozen solid. In fact, all the clothes had frozen solid.

Now, as you might suspect, pinning clothes to a line requires dexterity. Pinning clothes can not be done while wearing bulky mitts. Pinning clothes to a line requires fingers – fingers that quickly become numb and useless when exposed to wind and to frozen underwear, even at a relatively warm -6 C (+21 F). After a few minutes I retreated to the cabin to thaw my fingers. Eventually though, after a few trips out to pin, and a few trips back to thaw, all the clothes were hanging from the line. I sat down at the table to enjoy a mug of tea. The laundry seems to be under control.

Unfortunately the wind died a few hours after pinning our clothes to the line. Even nine hours later, all laundry except the pillow cases remained stiff as that proverbial board. Maybe we’ll have better success next time. Any way, laundry day was now over. In all the readings we had done about the “how to” and romance of isolated cabin life in the bush, no one ever mentioned how difficult laundry day would be. Then again, no one ever cautioned us against urinating in the outhouse, either.

On March 19, It now seems that perhaps we won’t need to cut much more wood. Today brought a strong southwest wind (30 km/hour; 20 miles/hour), and afternoon temperatures of minus 12 C (+10 F). We sit comfortably warm in the cabin as much as a metre (three feet) away from the stove. The ice above the narrows is slumping in a large semi-circle nearly from shore-to-shore. The days are getting longer. The sun is definitely warm. The weather report on CBC indicates plus temperatures (above 32 F) for many of the southern NWT places such as Hay River, Fort Smith. Even the western Arctic Coast temperatures are getting up in the minus teens (five or so F). It is almost 5:00 p.m., but the sun is still high in the sky.