- Joined

- Aug 21, 2018

- Messages

- 1,812

- Reaction score

- 4,603

Kathleen and I have often given a slide show on our expeditions in northern Canada, with an emphasis on natural and cultural history. Many of you will have seen some of these images in my previous trip reports, but the emphasis here is quite different. I hope you enjoy it. Glenn suggested that this presentation of best presented in this forum, so that's what I have done. Throughout this thread, I speak in regular font, while italics represents Kathleen's part of the presentation. So here goes.

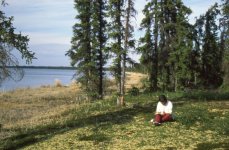

We are very happy to be here to talk about our experiences travelling throughout the far north of Canada from 1990 to 2019. It is a landscape that we truly love -- and love to talk about. It’s also a landscape that is largely unknown, and regrettably, undervalued, even by most Canadians. We look forward to sharing with you this region’s natural history: its plants, animals, geology, beauty, isolation, and history. We feel particularly fortunate that we have had the opportunity to enjoy this almost uniquely Canadian experience in summer by canoe, and in winter by snowshoes.

We also hope that we can convey the satisfaction of being alone in this landscape, which to us in so many ways represents a 'Land of Light'

Even more importantly than the light and beauty, however, we find that we are irresistibly drawn to the peace and renewal that we find in 'Canada's Northern Oasis.'

The Northwest Territories comprises approximately 1,200,000 sq. km (465,00 sq. miles). Nunavut; almost 2,000,000 sq. km (775,000 sq. miles). This is 5.5 times the size of Saskatchewan, and in all this land, in 2020, there were only 84,000 people. By comparison, the combined population of just Prince Albert and Moose Jaw also equals nearly 84,000 people! During our presentation, we will present a collage of images collected across northern Canada, including the Seal River down to Hudson Bay, the Coppermine River and Anderson Rivers to the Arctic Ocean, the Snowdrift River along tree line east of Great Slave Lake, and the Thelon River, which flows across the Barren Grounds. We will also describe the return of Spring from our vantage point in a small cabin at Colville Lake, just north of the Arctic Circle, which, at 66.5 degrees north, is the lowest latitude at which the sun remains above the horizon for 24 hours.

Water is a major component of Northern Canada. Fresh water comprises 21% of the area of Nunavut and 13.5% of the area of NWT. The canoe, besides being a most practical way to travel through this land, also offers the most historically satisfying experience, because it played such a vital part of Canadian heritage.

The late Pierre Trudeau wrote an essay when he was 25 years old in which he says. "What sets a canoeing expedition apart is that it purifies you more rapidly and inescapably than any other. For it is a condition of such a trip that you entrust yourself, stripped of your worldly goods, to nature… For throughout this time your mind has learned to exercise itself in the working conditions which nature intended".

Tonight we invite you join us to experience the joy and isolation of travelling along the rivers and lakes of Northern Canada.

But, rivers and lakes run free for only 4-5 months. Most of the year they remain frozen. One needs to follow the winter trail to truly understand and know the character and soul of Canada's vast, seemingly limitless northern landscape. We begin our presentation on the winter trail.

In 1999 we rented a cabin just beyond the Arctic Circle at 67 degrees north at the north end of Colville Lake. We flew away from Inuvik in a Twin Otter on January 31st at -400 C. We landed in this cove 200 m (200 yards) from our cabin, which we had never seen before. We had flown to this place with the simple faith that we would find a comfortable home. The pilots began to unload our food gear onto the ice. I was anxious to see what the cabin was like. I put on my snowshoes, and began walking toward the point on which our cabin stood.

I was so happy find that our 14 x 14 foot cabin was very well-made, cozy, and inviting. We would indeed have a very comfortable home for the next 4 and a half months.

During that first week in February we spent a lot of time organizing gear and hibernating. We usually slept late, and then lingered by the fire, enjoying our oatmeal, sipping tea, and toasting bread on the wood stove. The morning sun streams through the south-facing window, and we bask in its light. At temperate latitudes the sun rises in the east and sets in the west. We all know this generality. In the arctic, however, in mid-winter, the sun first rises nearly due south near mid-day, and sets soon afterwards, also nearly due south.

We commonly saw small groups of caribou wintering near our cabin. Caribou are superbly adapted to winter. Because the heat of out-flowing arterial blood is exchanged with veinous-blood heat, caribou body temperatures remain at 40 degrees C (104 F). even though leg temperatures fall to only 10 degrees C (50 F). Caribou subsist mostly on lichens, which they are able to digest with the enzyme lichenase. Lichens are low in protein, which is useful for caribou, because a low-protein diet requires little water for digestion.

Feb. 22. The sparkling white lake, the white spruce spires reaching into the deep, blue sky, and the branches of the aspen trees, delicately white-covered with hoarfrost, make for a breathtaking scene. And ALL of it is ours to enjoy.

Hoarfrost forms when the air is completely saturated. That is, when there is more moisture in the air than the air can carry. If the air is sufficiently dry, moisture can remain suspended in the air at temperatures well below zero degrees. In fact, pure water can remain suspended in clean at temperatures close to minus 40 degrees.

Our canoe waits for Spring break up, when we will paddle 4 weeks and 550 km (350 miles) down the Anderson River to Liverpool Bay on the Arctic Coast.

(Note: I will post more tomorrow.)

We are very happy to be here to talk about our experiences travelling throughout the far north of Canada from 1990 to 2019. It is a landscape that we truly love -- and love to talk about. It’s also a landscape that is largely unknown, and regrettably, undervalued, even by most Canadians. We look forward to sharing with you this region’s natural history: its plants, animals, geology, beauty, isolation, and history. We feel particularly fortunate that we have had the opportunity to enjoy this almost uniquely Canadian experience in summer by canoe, and in winter by snowshoes.

We also hope that we can convey the satisfaction of being alone in this landscape, which to us in so many ways represents a 'Land of Light'

Even more importantly than the light and beauty, however, we find that we are irresistibly drawn to the peace and renewal that we find in 'Canada's Northern Oasis.'

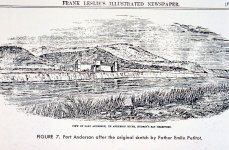

The Northwest Territories comprises approximately 1,200,000 sq. km (465,00 sq. miles). Nunavut; almost 2,000,000 sq. km (775,000 sq. miles). This is 5.5 times the size of Saskatchewan, and in all this land, in 2020, there were only 84,000 people. By comparison, the combined population of just Prince Albert and Moose Jaw also equals nearly 84,000 people! During our presentation, we will present a collage of images collected across northern Canada, including the Seal River down to Hudson Bay, the Coppermine River and Anderson Rivers to the Arctic Ocean, the Snowdrift River along tree line east of Great Slave Lake, and the Thelon River, which flows across the Barren Grounds. We will also describe the return of Spring from our vantage point in a small cabin at Colville Lake, just north of the Arctic Circle, which, at 66.5 degrees north, is the lowest latitude at which the sun remains above the horizon for 24 hours.

Water is a major component of Northern Canada. Fresh water comprises 21% of the area of Nunavut and 13.5% of the area of NWT. The canoe, besides being a most practical way to travel through this land, also offers the most historically satisfying experience, because it played such a vital part of Canadian heritage.

The late Pierre Trudeau wrote an essay when he was 25 years old in which he says. "What sets a canoeing expedition apart is that it purifies you more rapidly and inescapably than any other. For it is a condition of such a trip that you entrust yourself, stripped of your worldly goods, to nature… For throughout this time your mind has learned to exercise itself in the working conditions which nature intended".

Tonight we invite you join us to experience the joy and isolation of travelling along the rivers and lakes of Northern Canada.

But, rivers and lakes run free for only 4-5 months. Most of the year they remain frozen. One needs to follow the winter trail to truly understand and know the character and soul of Canada's vast, seemingly limitless northern landscape. We begin our presentation on the winter trail.

In 1999 we rented a cabin just beyond the Arctic Circle at 67 degrees north at the north end of Colville Lake. We flew away from Inuvik in a Twin Otter on January 31st at -400 C. We landed in this cove 200 m (200 yards) from our cabin, which we had never seen before. We had flown to this place with the simple faith that we would find a comfortable home. The pilots began to unload our food gear onto the ice. I was anxious to see what the cabin was like. I put on my snowshoes, and began walking toward the point on which our cabin stood.

I was so happy find that our 14 x 14 foot cabin was very well-made, cozy, and inviting. We would indeed have a very comfortable home for the next 4 and a half months.

During that first week in February we spent a lot of time organizing gear and hibernating. We usually slept late, and then lingered by the fire, enjoying our oatmeal, sipping tea, and toasting bread on the wood stove. The morning sun streams through the south-facing window, and we bask in its light. At temperate latitudes the sun rises in the east and sets in the west. We all know this generality. In the arctic, however, in mid-winter, the sun first rises nearly due south near mid-day, and sets soon afterwards, also nearly due south.

We commonly saw small groups of caribou wintering near our cabin. Caribou are superbly adapted to winter. Because the heat of out-flowing arterial blood is exchanged with veinous-blood heat, caribou body temperatures remain at 40 degrees C (104 F). even though leg temperatures fall to only 10 degrees C (50 F). Caribou subsist mostly on lichens, which they are able to digest with the enzyme lichenase. Lichens are low in protein, which is useful for caribou, because a low-protein diet requires little water for digestion.

Feb. 22. The sparkling white lake, the white spruce spires reaching into the deep, blue sky, and the branches of the aspen trees, delicately white-covered with hoarfrost, make for a breathtaking scene. And ALL of it is ours to enjoy.

Hoarfrost forms when the air is completely saturated. That is, when there is more moisture in the air than the air can carry. If the air is sufficiently dry, moisture can remain suspended in the air at temperatures well below zero degrees. In fact, pure water can remain suspended in clean at temperatures close to minus 40 degrees.

Our canoe waits for Spring break up, when we will paddle 4 weeks and 550 km (350 miles) down the Anderson River to Liverpool Bay on the Arctic Coast.

(Note: I will post more tomorrow.)

Attachments

Last edited: